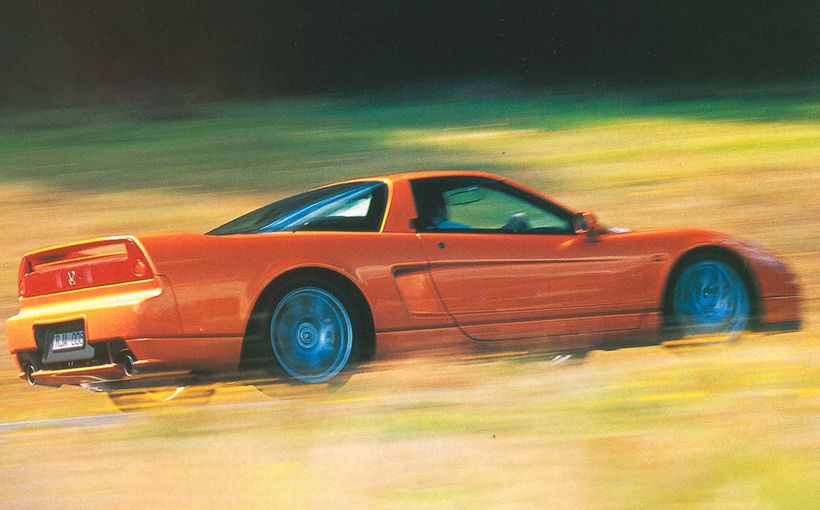

There's a lightness to this car, a smoothly satisfying flow that rewards precision. The NSX is undemanding, yet hugely capable. It darts and rushes with none of the heavy machismo of the musclebound Italians. You drive this one with the brain and fingertips. With a Ferrari or Lamborghini it is bravado and biceps.

In place of brute strength and sweat the newcomer commands poise and subtlety. It seeks fine, measured inputs; ridicules the clumsy and ham-fisted.

But if the chassis barely whispers, the engine screams.

It's faster than a Testarossa this car, more potent than a Carrera 2.

Squeeze the throttle and the senses are overwhelmed. Behind your shoulders is a cache of weapons-grade torque, exploding in a glorious V6 wail that rises, incredibly, all the way to 8000 rpm . There is no seam in this wall of power. At around 5800 revs the VTEC cam timing is actuated. It's felt only as increased velocity.

Anyone who doubted Honda's ability to build a genuine supercar should look no further than the raw performance data ~ zero to a hundred kays in 5.6 seconds, a standing metric quarter-mile in the high 13 second bracket ...

But figures don't tell the whole story.

Honda's final production version of the NSX supercoupe marks the beginning of a dynasty unthinkable even two years ago. A dynasty of Japanese engineering versus European pedigree, at the uppermost limits of the supercar league.

But let's go back to the beginning ...

When Wheels tested the prototype of the NSX at Honda's Tochigi Proving Ground last September, the men from Research and Development . were candid. They still had some work to do, they said, on body stiffness and interior packaging. Then there was the matter of the unfinished VTEC 3.0 litre V6 engine. It promised significantly more performance than the conventional 3.0 litre sohc, quad-valve unit in the prototypes.

As expected, the final incarnation of the NSX turned out larger than those pre-production cars, the ones you saw at the Sydney and Melbourne motor shows. The enlargement had prompted talk of increased weight and complexity, a fattening of the original concept, said the knockers. Would it be a soft, flabby car to match rich American physiques?

As it stands, the production car arrives with a wheelbase 30 mm longer than the show car, with stretched fore and aft overhangs to accommodate a real luggage compartment and a spacesaver spare. But we need not have worried about an adulteration of the initial concept. The production NSX, with air-conditioning, anti-lock brakes, traction- contro l, power-steering and electric everything, weighs just 1370 kg. The new Ferrari 348 is 23 kg heavier. In that context, the NSX is commendably trim.

According to the president of Honda's R&D department, Hiro Shimojima, the unrelenting aim of his NSX project team was to produce the most sophisticated modern sports car in the world, one that can be driven by anybody. After three days hard driving we believe Honda has been successful.

Due to the low scuttle height and seating position, the ignition key in the NSX is quite a stretch, but its operation is rewarded with a delightfully crisp exhaust note, and very urgent throttle responses. Clutch effort is low, and the engagement span long and smooth. The stubby gearlever moves through contrasting short throws, with a pleasantly light and positive action. As the car moves away from rest, the unassisted steering lightens instantly. The first surprise is the compliant ride, the second one the comparative lack of hard edges in the feel of the controls. At moderate speeds the car is more like an Accord than something from Maranello.

As the tachometer needle swings round the dial, the sounds from behind the shoulders change from a muted intake gurgle to a mellifluous bellow as the revs bui ld. The power delivery is progressive, with no perceptible steps in output. As the ride is so gentle and the controls so light and direct, the experience of driving fast is somewhat understated. It's only when you glance at the speedometer and notice you're running about 20 km/h faster than you could manage in any comparable car that the message begins to sink in.

Without any substantial weight on the front end, the NSX turns in decisively. Its relatively long wheelbase damps the tendency found in some contemporary mid-engined designs to rotate on a trailing throttle, and exit speeds from corners are limited mainly by tyre grip. The tyres are specially made 50 series Yokohama A-022s, which work extremely well with the NSX's excellent suspension disciplines. The gloriously detailed alloy underpinnings allow quite a bit of wheel travel, and even a surprising degree of roll, but they keep the wheels squarely presented to the surface so handling is predictable and tyre wear even.

It's said low mass is its own reward, and the Honda is living testimony to it. It accelerates, brakes and corners in a fine smooth flow, without any of the lunging exertions you encounter in tightly strapped heavyweights.

There's a fluidity to the NSX that rewards smooth inputs with quicker times. A high redline doesn't hurt track performance either, providing long blasts of power in the intermediate gears before you need to flick the short lever through the gate. Low flywheel mass and dazzling throttle response turn double-clutched sh ifts into highly satisfying co-ordination games, while the massively powerfu l, fade-free brakes provide vastly reassuring retardation.

Fast and safe though the NSX is, it doesn't take to clumsy inputs. With the fabled low polar inertia of its mid-engined configuration, the car is easily persuaded to change direction. It will translate brutal inputs into brutal responses. Also, it demands very quick corrections when coaxed into oversteering slides, a practice somewhat complicated by the degree of roll allowed by the relatively civilised spring and bar rates. If the driver does not steer out of his opposite-lock correction very promptly, the car will snap straight and hop from one pair of wheels to the other in the flit of a hummingbird's wing, and you can find yourself in the classic over-corrected slide.

However, this need never happen to a driver who explores the NSX's gentle nature. Control the body roll (which is not excessive) with progressive inputs, and the rewards are high levels of grip, superb turn-in, and great traction. Just the simple practice of trailing the brake into a bend - gradually trading braking force for cornering force - has the car feeling nailed to the surface. There is a small degree of loading -up in the steer- ing as you pull the car off its straight ahead bearing, but the wheel never puts up much of a fight, and you can dial in more lock, or even stab the wheel to opposite lock if necessary, without being a champion arm-wrestler.

In fact, a driver need never contemplate vehicle control at the limits providing Honda's traction control system is switched on. This will detect the rotational differences at the wheels, compare them with steering angle and vehicle yaw rate, and then reduce power to bring the car back within the defined handling envelope. In hard cornering this manifests itself as an intermittent interruption of power, something like the rev-limiter which cuts in at 8300 rpm.

Traction control wasn't necessary on the racetrack, because the limited-slip diff handled all the traction variations, but it will prove invaluable in extreme weather conditions.

Technically, the NSX is a fascinating exercise in fundamentals like power to weight ratio and packaging. Unlike the conventional supercars, Honda wanted everyday practicality, too. And that meant packaging problems with the mid-engined rear-drive format. Honda stuck to its guns because of the distinct advantages it offers - like a low centre of gravity and reduced yaw inertia values .

Needing a power-to-weight ratio of 3.7 kg/kW in order to meet competitive 0-100 km/h and standing 400 metre acceleration times, Honda chose a combination of a relatively small , normally aspirated 3.0 litre V6 powerplant and a • light alloy body to do the job. But neither of these two major components would guarantee a world-beating car without extensive development and adaptation. That's the real story behind the NSX.

First, the engine. Honda has unrivalled experience extracting high specific power output figures from engines - just ask Ayrton Senna - but in the case of the NSX, the engineers needed decent torque at moderate engine speeds too, lest the thing become an embarrassment in city traffic. The solution was a variable length intake tract, controlled by a valve that opens at 5000 rpm, and VTEC, or variable valve timing and lift. In the dohc 24-valve V6 it means having three cam lobes for each pair of valves, instead of two.

Considering the inlet side of one cylinder as an example, the two outer cams (using slightly different timing for swirl propagation) operate the two inlet valves in the normal mode via their respective followers , while the centre high-lift lobe freewheels away at its follower, damped by a lost motion spring. As the engine reaches 5800 rpm, a hydraulic piston in the rocker shaft is instructed to lock the rockers together. Now the high-lift cam takes over the actuation of both valves, operating them in its wilder configuration.

The result is an engine that revs joyously to the 8000 rpm redline (7500 rpm on the auto-trans model), developing an extra 15 kW in the process. The net total is 201 kW at 7100 rpm, enough to propel the car to 265 km/h. Fairly radically oversquare bore and stroke dimensions help keep piston speeds down at the car's elevated redline, with lightweight titanium connecting rods doing their bit to reduce inertia. The automatic-equipped car is somewhat less powerful, making 188 kW at 6600 rpm, but both cars produce 285 Nm of torque at 5300 rpm. That 265 km/h top speed may not equal the maximum velocities of the biggest of the exotics - the cars Honda's R&D men call "monsters" - but its stunning acceleration times are achieved without excessive fuel consumption.

Honda decided an aluminium body was necessary to maintain a good power-to-weight ratio with a normally aspirated engine. It achieved the desired objective, and also gave the NSX an overall integrity better than that of a steel car.

The relatively long wheelbase allowed a long passenger cabin, but also gave distinct advantages in terms of stability. Fifteen inch front wheels (the rears are 16-inchers) were fitted to increase the footbox volume.

Extensive wind tunnel testing indicated a fastback rear window provided better aerodynamic performance than the "tunnel-back" of Ferrari and Toyota. It also offered far better visibility because the flying buttress C-piilars commonly used on that format are deleted. Unfortunately, the raked back window also generated greater tail lift, which necessitated the fitting of a tail spoiler. Honda uses that rear window as an engine cover, in combination with another parcel- shelf-like inner cover beneath it. In addition, a double-glazed vertical panel between the engine compartment and passenger cell isolates occupants from noise and heat.

With a focus more on balancing overall drag performance with crosswind resistance and lift characteristics, the R&D team painstakingly arrived at the best amalgamation possible of all those properties. They achieved a Cd figure of 0.32, with overall yaw moment (Cym) of 0.24, and lift coefficient (CL) of 0.05.

The style, says designer lchinose, was based on the F-16 Falcon fighter plane. If that sounds improbable, then consider that the interior was based on a fighter pilot's "intell igent helmet" concept. The result is a cabin of remarkable simplicity and elegance, with excellent all-round visibility, and none of the claustrophobic shrouding typical of midengined packaging.

In the real world, the NSX is admirable. It will virtually banish the pain from exotic car ownership. If the vehicle's durability is close to Honda's normal standard (and we bet it is), this could be one of the world's most practical supercars. It even has a 500 km cruising range.

When you consider the car's leadingedge chassis dynamics and 67 kW per litre engine performance, its head-turning styling and superb build quality from a largely hand-crafted line at Honda's Tochigi R&D facilities, the car seems worth its pricetag. By the time it arrives in Australia, probably next February, it will cost around $135 ,000 - or $20,000 less than Porsche's Carerra 2.

Now that Honda has a grand prix pedigree equal in achievement, if not vintage, to that of Ferrari, no-one should seriously question the company's supercar credentials. Anyone who has driven the NSX is certainly not quibbling about the company's technical capabilities; the car is, after all, clearly one of the best of its kind ever made.

Go Back in Time with the Wheel Archive. Get FREE access to 5 years of Wheels archive content now!

Protect your Honda. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.