When Sir Jack Brabham famously won his third and final World Driver’s Championship in 1966 in a Brabham BT19, he became the first - and so far only - driver to do so in a F1 car of his own design and construction. However, there was another Aussie who also scored a major international victory in a car he designed and built himself, only this one was based on a V8 Falcon ute competing in one of the world’s most prestigious off-road races – the legendary Baja 1000.

The name Jim Hunter may not be as well-known or revered as Sir John Arthur Brabham AO, OBE, but what this ‘other’ Aussie achieved in 1987 ranks as one of the greatest unsung victories in the history of Australian motor sport. He became the first Aussie to win the Baja 1000 (and in a brand new car in its first competitive outing) after a bruising battle in the Mexican desert, yet the history-making feat barely rated a mention in his homeland.

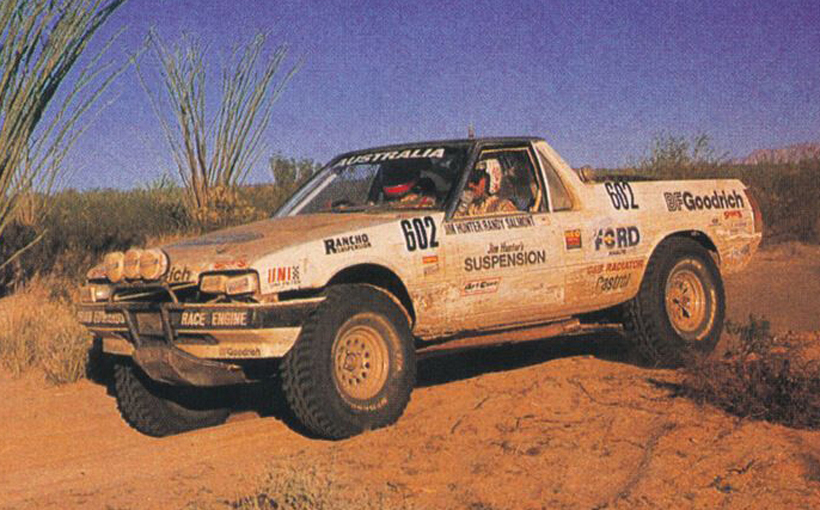

Hunter’s hand-built XF Falcon ute, powered by a 400bhp 351cid Cleveland V8, had barely turned a wheel before its Baja baptism of fire. Not only that, the tough Aussie machine standing tall on huge 35 x 12.5 R15 BF Goodrich tyres, featured innovations like torsion bar suspension and an automatic trans-axle that stunned battle-hardened Baja regulars – and which have since been widely copied.

His historic achievement in Mexico should not be underestimated. The 1987 event was conducted over a typically cruel, car-busting course which started and finished in the northern Mexico city of Ensenada. The field, which comprised hundreds of different vehicles spread across dozens of classes, crashed and bashed its way around a sadistic near 1000-mile loop of the barren Baja Peninsula. The event ran non-stop, reaching altitudes of 2500 metres in the mountains and top speeds of up to 240km/h!

Just surviving the many brutal hazards that lurk between the cactus, boulders and rattlesnakes of Baja each year deserves a medal. What makes the event even tougher - and at times life-threatening - is the dangerous antics of Mexican spectators who often set up traps along the route. Piles of rocks, logs, old fridges and even steel spikes driven into the ground can trigger spectacular high-speed crashes that amuse and delight the locals. Many competitors have also been pelted with large rocks and some have even finished with bullet holes through their bodywork!

Yes, Baja is not for the faint-hearted. Jim Hunter’s victory in Class 6 for production-based cars, which he achieved with US co-driver and experienced Baja racer Randy Salmont, came after nearly 24 hours of flat-out driving in what was a superhuman performance. They started at 8am on a Saturday, raced hard throughout the day and night before crossing the finish line at sunrise on Sunday. Less than 100 of the original 400-plus starters made it to the finish...

This is an inspirational story about an Aussie underdog who with little more than ingenuity and determination took on the best American off road racers with a self-funded Australian-made car - and beat them at their own game.

The Road to Baja

By the mid-1980s, while running his own successful suspension tuning shop in Sydney, Hunter’s focus had shifted from bitumen circuit to off-road racing. He started competing in a buggy before progressing to an imported Chevy Blazer. This was a specialised off-road racer scratch-built by Parnelli Jones in the US featuring a full chrome moly space-frame chassis, lightweight plastic body panels, enormous suspension travel and a thumping 350cid small block V8.

Hunter thought such a crowd-pleasing beast would be a good promotional tool for his business (Jim Hunter's Suspension). After finishing an impressive second outright in the 1986 Yokohama 300 at Griffith in northern NSW, Jim took the advice of visiting US off road legend Rod Hall and shipped the Blazer to the US to have a crack at the Baja 1000. Hall helped out with some useful contacts, including California-based Randy Salmont, which allowed Hunter to get his first taste of Baja.

He didn’t win, but that wasn’t a realistic goal for a rookie who was also on a fact-finding mission. The intrepid Aussie admitted he was bitten hard by the ‘Baja bug’ on his first visit, which developed into a single-minded obsession of returning to Mexico with a car of his own design - and winning!

In an interview I did for Australian Muscle Car magazine in 2003, Hunter explained how the XF Falcon ute project was born and why the car’s home-grown engineering stunned the Americans.

“On the way home on the plane (after Baja 1986) I was getting pretty excited about this off-road racing. There were things on the American-built cars I reckoned I could improve on so I got out a sheet of paper and I wrote down all the Blazer specs and tried to figure out how I could improve on all that. I went through everything and came up with a plan for my own off-road racer.

“I’m an aircraft engineer by trade. I used to work for Frank Matich building his Formula 5000 racing cars and I also worked for John Joyce at Bowin building F5000 cars for John Harvey and John Leffler. I learned a lot about building racing cars with those guys, like suspension design and steering geometry, torsional stiffness, all that type of thing so I was confident I could do the job.

“Then I had to figure out what body I’d put it in. I told a mate of mine who worked in the car wrecking game that I was looking for a ute, mainly because of the freedom if offered for chassis construction at the back. The lay-out of a ute is basically an engine and driver’s compartment with nothing in the back, so you could cut it all out to build a chassis which is the way the Americans do them. He said he had just the thing - a stolen and recovered Falcon. I went out and bought that for $1000 and away we went.”

Hunter started building his Baja challenger in early 1987. It was a tough slog to meet a tight deadline, working 18 hours a day for six months non-stop with invaluable help from mates in their spare time. Jim’s wife often brought food to ensure her hubby didn’t starve and she often had their kids in tow, to confirm that their dad’s long absences from home were indeed for a worthy cause!

The re-engineering of the XF Falcon ute was extensive, starting with a total strip-down to the bare body-shell which was then gutted, leaving only the basic cabin structure, outer shell and chassis rails within which Hunter fabricated a state-of-the-art chrome moly space-frame with long-travel independent suspension.

Just working out the steering geometry took three days, because it had to go through a full 16 inches (400mm) of wheel travel without any bump steer. The solution was ensuring that the front suspension’s lower control arm angle and length had to be the same as the steering arm so that they moved up and down like a parallelogram.

Three innovations which stunned the Americans was the use of torsion bars instead of coil springs, attaching the automatic transmission directly to the differential and mounting the engine as low as possible, as Hunter explained.

“It was easier to get the amount of suspension travel I wanted out of a torsion bar rather than a coil. In those days, the way the Yanks were getting more than 12 inches (300mm) of suspension travel was with multiple (stacked) coils which seemed pretty agricultural to me. We built the ute with one torsion bar per wheel and anti-roll bars front and rear to control the body roll, because it sat pretty high.

“The (independent) suspension was really like a classic open-wheeler racing car design, (hub carrier uprights with double wishbones at the front and trailing arms with twin parallel lower links at the rear) with adjustable brake bias (front to rear). I wanted to use components that were readily available so I used stuff like front uprights from a Toyota HiAce, which were just bullet-proof.

“In off-road racing you need as much weight as you can in the back (ideally a 50/50 weight distribution to avoid nose-heavy landings) and the whole trick to that car was putting the (auto transmission) in the rear because it was really heavy.

“Craft Diffs got a Ford nine-inch diff for us and chopped the axle tubes off it and turned it into an independent rear-end with Jaguar in-board disc brakes. We rigidly mounted that diff in the chassis then we made up an adapter plate and bolted the Turbo 400 (automatic transmission) directly to the front of the diff. Then we made up a jack-shaft like you see in a boat going directly from the back of the engine through the cockpit to the transmission. It was my own design and when the Americans first saw it they shook their heads and said ‘how simple is that?’

“The other thing I figured out was that because you had to raise these cars right up in the air to get the right amount of suspension travel, that big 351 Cleveland V8 was getting higher and higher. We actually designed the chassis so that the engine was mounted low, so that the centre of gravity was also low. The car just steered and stopped and did everything superbly.

“They thought all that was amazing and ingenious, whereas I thought it was just good engineering practice and basic common sense. They also thought the vehicle had been built way too light and didn’t think we would reach the finish. The Yanks were building stuff stronger and stronger which meant it got heavier and heavier and I figured that’s why they kept breaking stuff on their cars.”

Down Under Thunder

With the Baja 1000 fast approaching, Hunter only had time for a brief shakedown on a property in Sydney’s west before the wild-looking Falcon ute had to be flown to the US in the belly of a Qantas 747. That presented even more unique challenges.

The tapered shape of the Jumbo’s cargo hold meant the big-footed Falcon was too wide to fit, so Hunter had to build a special supporting frame that would allow the ute to slide in upside down instead with its tyres pointing skyward. He proudly attached a ‘Down Under Thunder’ sign and when it was unloaded in the US, the freight handlers were all laughing as they believed everything had to be upside down in Australia!

Co-driver Randy Salmont arranged for a tow vehicle and trailer to transport the freshly-built Aussie racer to his LA garage for final preparations. There was just enough time for another quick shakedown, this time in some open country north of LA, before they headed down to Mexico for the start at Ensenada.

As you would expect, Hunter and Salmont took a conservative approach (well, certainly at the start), given that they were about to tackle a notoriously tough off-road race in a brand new and virtually untested vehicle. As Hunter described it, their catch-cry was ‘egg shells’ (as in driving on them) because they had to race smart and be patient, particularly given that there were dozens of vehicles in Class 6 and the unknown Aussie ute would be starting from the back because it could not be given a seeding position.

Due to the project’s time constraints and minimal pre-event testing, some engine cooling issues and electrical gremlins emerged during the early stages of the race. However, they were never serious enough to stop them in the heat of the day and both problems abated at night due to much cooler temperatures.

The XF ute proved to be more than strong enough for Mexico and mighty competitive. All day and night Hunter and Salmont were locked in a fierce three-way fight for Class 6 honours with the wild 1955 V8 Chevy of multiple class winner Larry Schwacofer and the big V8 Camaro driven by Bill Russell. Mike Magda’s race report in Chevron Publishing’s 1997-98 Australian Off Road Yearbook described their gladiatorial clash:

“From the start the Falcon experienced overheating problems. Even though he stopped many times to throw water over the radiator, Salmont led Larry Schwacofer (‘55 Chev) by two minutes when they reached Borrego. The overheating problems continued with Hunter behind the wheel. At one point he had to stop for 30 minutes to cool the engine. When Hunter returned to Borrego for refuelling he was passed by Bill Russell’s Camaro. Salmont took over the driving chores for the trip up to Mike’s Sky Ranch (in the mountains).

“That’s when the electrical problems started. When the car stalled for the first time, a Class 5 entrant stopped to provide a jump start. It (the ute) soon stalled again. This time Schwacofer offered to jump-start the wounded Falcon, if they would give him a 10-minute head start. ‘Just sitting there the engine started to overheat again, so I could only give him about six minutes,’ admits Salmont.

“Schwacofer broke down on the beach when the Falcon, now driven by Hunter, passed by. ‘That just left the Camaro,’ continues Salmont. ‘Just before Santo Tomas we passed them in a water hole and flooded them out, but then they ate us alive on the straightaway. They must’ve had 150 horsepower on us.’

“Coming into Ojos Negros, Hunter again blasted through a water hole just as the Camaro was tip-toeing across. Again the water spray flooded out Russell’s big Chevy. The Falcon was able to hold off another late charge by Russell to win by just seven minutes in a time of 22:14 (22 hours and 14 minutes). Scwhacofer finished another 43 minutes back.”

It was a remarkable and unprecedented Baja 1000 victory for an Aussie driver in an Aussie car – a Falcon ute that is! This was at a time when imported Japanese brands were starting to eat into a light commercial vehicle market long dominated by Falcon and Holden utes. A victory in the world-famous Baja 1000 could have been marketing gold for Ford in pushing its ‘built tough by Australians for Australians’ mantra.

However, after waiting months before agreeing to “sponsor” the Aussie Baja campaign, Hunter said Ford Australia’s support amounted to “30 spark plugs and a battery” and he gave up in despair. Of course, when he triumphantly returned from Mexico, guess who wanted to feature his ute in its latest advertising campaign? We don’t need to tell you Jim’s answer.

Even so, the XF Falcon did end up displaying a big Ford logo at Baja because Ford reps in the US just loved the ‘Crocodile Dundee pick-up’ and offered some vital logistical support during the event. According to Hunter, conquering Baja’s many unique challenges provided a career high that could never be matched.

“The scary apart about it is the beaches are so flat and so long our headlights couldn’t focus on anything, so you had no depth of field. The only things you could see were the gauges - that was the only light. You could have been in space. It was so smooth there was no sense of motion, except when you looked at the tacho and saw it sitting on 6000rpm so you knew you were doing about 240km/h. Then you’d start to panic because you knew when you got to the end of the beach you were going to have to react within the length of your light beams!

“The car to beat was Russell’s Camaro. It had a 400ci (6.5 litre) Chev V8 in it and anytime there was a straight he just mowed us down. In the end we beat him on handling. The final run to the finish at Ensenada was along the main (bitumen) highway that runs through the centre of Baja. It was a distance of about 20 miles (32 km) and the handling and steering of our car just killed him. We were doing about 240km/h in top gear and on those tall tyres we were just going from one big, high-speed power slide to another. I felt fully in control because of my road racing background and the way the car was set up. Randy was just blown away by it. He couldn’t believe the car could go so quickly on tarmac.

“(After the race) Randy had had it. He’d already been there and done that at Baja many times so he was ready for bed, but I was on the biggest high of my life. I just couldn’t sleep. I was walking around Ensenada, went and had some breakfast, spoke to a few people, I was so wired. I was dying to ring home but it was hard to find a phone in Ensenada. When I finally rang and told everybody we’d won, well, the cheer down the phone was just, oh, I’ll never forget that. It was just fantastic. It was a very satisfying win because there were about 40 cars competing in our class.

“We did something that no other Aussie had ever done and still hasn’t done. It was an Aussie ute that had been designed here and built here with Aussie ingenuity and a lot of hard effort. We beat the Yanks at their own game.”