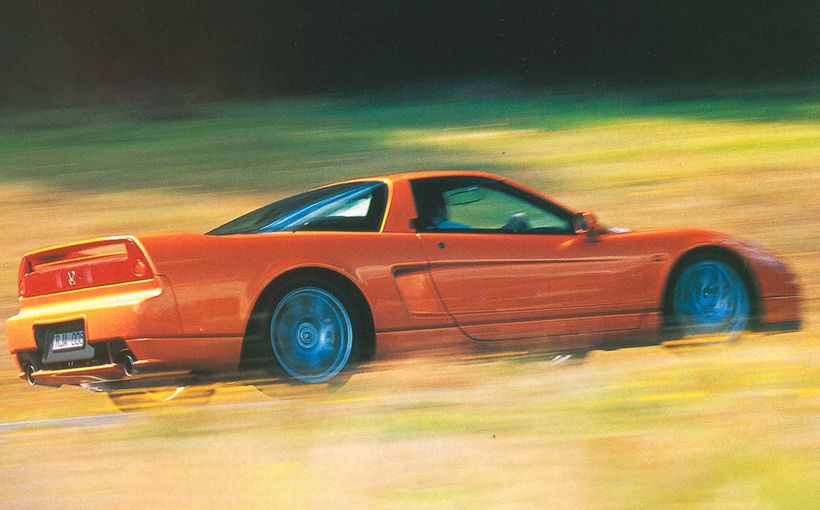

Honda NSX: Body by Honda. Soul by Senna.

The first generation Honda NSX (1990-2005) may not possess the raw Italian passion of a Ferrari or Lamborghini. However, Japan’s first mid-engine supercar, which also raced with success in Japan, at Le Mans and even Bathurst, features a unique element in its DNA that no other can match - Ayrton Senna.

Although reference is often made to the brilliant Brazilian - who won three world F1 titles with Honda-powered cars - having input in its design, the depth of Senna’s involvement with factory engineers during the NSX’s painstaking development process is often overlooked.

Senna, a perfectionist, is still revered today by Honda as an inspiration. He convinced its engineers to substantially stiffen the NSX’s all-aluminium unitary body-chassis (reportedly by up to 50 per cent) after track-testing a near production-ready prototype at the Honda-owned Suzuka GP circuit in Japan in early 1989.

He also played a pivotal role in refining the car’s sublime suspension tuning later that year, when Honda’s R&D department regrouped at the old Nurburgring circuit in Germany using the full 28km original length with its infamous 173 corners per lap.

Before his tragic death at Imola in 1994, Senna made 161 GP starts resulting in 41 wins, 80 podiums and 19 fastest laps. His staggering record of 65 pole positions stood for more than a decade.

The Brazilian’s qualifying speed was extraordinary. His wet weather driving beyond comprehension. And his genius behind the wheel was matched by intimate technical knowledge of what he was driving and an unwavering commitment to perfect its performance.

Given that the NSX (New Sportscar eXperimental) is often derided by Italian sports car purists for being too comfortable, too competent, too refined, too - dare we say it - perfect, then it does in its own unique way pay tribute to the late F1 great who had a hand in its creation.

Visually, it was distinctly Japanese, distinctly Honda, with styling by the company’s chief designer Masahito Nakano. It stood only 1170mm tall, or 46 inches on the old scale, which was only 150mm or 6.0 inches taller than Ford’s legendary GT40 Le Mans winner. The Honda’s co-efficient of drag was just 0.32. A 2002 facelift would drop that to 0.30.

Honda wanted to showcase its state-of-the-art technology developed through its F1 programs (there’s that Senna connection again). The NSX was the first production car to use an all-aluminium unitary body, which was not only extremely rigid but also saved nearly 200kg compared to a steel equivalent. Kerb weight was only 1370kg.

The NSX also featured forged aluminium suspension components which saved another 20kg, mostly in unsprung weight. Suspension was F1-style upper and lower A-arms with coil-over shocks on each corner, plus anti-roll bars, electric power-assisted rack and pinion steering and big ventilated disc brakes at both ends with four-channel ABS.

Its 3.0 litre V6 was mounted transversely behind the cockpit for an excellent 43:57 weight distribution. It featured an F1 developed fly-by-wire (aka wi-fi) throttle control and bespoke all-aluminium cylinder block and heads with dual overhead camshafts, four valves per cylinder and Honda’s superb VTEC variable valve timing and lift technology, that ensured the engine’s combustion process was optimised regardless of rpm.

And there were plenty available, with a spine-tingling 8300rpm redline, helped by a critical reduction in rotating masses by the first use of titanium connecting rods in a production car engine. Such sky-high rev tolerance allowed the quad-cam 24-valve V6 to hit its power target with 202kW (270bhp) and 285Nm (210ft/lbs) of torque.

Originally offered with a choice of five-speed manual or four-speed automatic transmissions (hey, this was 1990) the manual version did deliver what was then benchmark supercar performance, with a 14.0 second standing 400m, 0-100km/h in 5.6 seconds and a top speed of 168mph (270km/h).

In 1997 the engine capacity was increased to 3.2 litres with power rising to 216kW (290bhp) and 305Nm (225ft/lbs). The added weight of a new six-speed close-ratio gearbox and bigger brakes was offset by body panels stamped from a new higher strength yet thinner aluminium alloy sheet. The NSX was given a minor facelift in 2002 before production ceased in 2005, after 15 years and global sales of more than 18,000 units.

A motor sport natural

Given Honda’s pre-eminence as a Formula One engine supplier at the time, the NSX was destined to appear on race tracks around the world including Japanese GT racing, the Le Mans 24 Hour sports car classic and the short-lived Bathurst 12 Hour.

After its launch in 1990, enthusiasts (mostly Japanese) were soon clamouring for more track-focused versions and Honda duly obliged with some lighter, faster limited editions exclusively for its domestic market. These cars provided the foundation for the company's NSX motor sport programs.

The NSX made three appearances in the Le Mans 24 Hour race. In 1994 three cars were entered in the production-based GT2 category prepared by the German-based Kremer Racing Honda. Team Kunimitsu Honda from Japan was in charge of one of the cars, with all three finishing the race claiming 6th, 8th and 10th places in GT2.

Three NSXs returned to France in 1995. This time Honda’s factory team fronted with two much faster experimental turbocharged versions entered in the prototype GT1 division, while a non-turbo NSX prepared by Kunimitsu was entered in GT2. The two turbo cars struck trouble but the non-turbo Kunimitsu car won the GT2 category and finished an impressive eighth outright.

In 1996 only one car was entered in GT2 by Kunimitsu, with the same driving squad that delivered its GT2 class win the previous year. However, they missed out on back-to-back victories, finishing third in class and 16th outright.

Not surprisingly, the Honda NSX was also successful in the Japanese GT Championship (1993-2004) and its Super GT replacement from 2005. It raced in increasingly modified form to exploit the category’s liberal technical rules, winning numerous driver and team championships in both GT500 and GT300 categories. The NSX is a hero car in Japan.

The Australian Connection: From Tasmania to Bathurst

The NSX got its Australian motor sport career off to a flying start, when Tasmanian Honda dealer and national sports sedan champion Greg Crick with navigator Greg Preece won the first and second Targa Tasmania tarmac rallies in 1992 and 1993.

Given its dazzling performances in the TT, it was no surprise to see an NSX entered in the short-lived James Hardie 12 Hour production car race at Mount Panorama in 1993. Following Mazda’s victory with a works-entered twin turbo RX-7 in 1992, race organisers decided to widen the vehicle eligibility list to attract more exotic thoroughbreds to the Easter Sunday battle.

The 1993 12 Hour was proudly billed as the ‘Battle of the Supercars’ because joining Mazda’s two-car RX-7 works attack were a Lotus Esprit, R32 Nissan GT-R, two Porsche 968CSs – and a Honda NSX.

The black Japanese supercar was owned and entered by wealthy Queenslander Ross Palmer, who through his Palmer Tube Mills company and its brightly coloured extruded steel tubing products (Tru-Blu, Red-Roo, Greens-Tuf) had been Dick Johnson’s major sponsor for many years. The NSX was backed by another PTM product called Dogbone, because of its similar-looking cross-section.

The NSX generated plenty of pre-race headlines thanks to 1987 World 500cc Motorcycle Champion Wayne Gardner being signed to drive alongside Ross Palmer and his brother Ian. Gardner, having ridden Hondas to both his world title and two enthralling AGP victories at Phillip Island, was one of the marque’s favourite sons. And having recently retired from GP racing, was in the early stages of a second motor sport career on four wheels.

Larry Perkins, who with Gregg Hansford would win the Bathurst 1000 in a Commodore later that year, claimed pole position in the turbocharged Lotus Esprit during Friday’s qualifying session ahead of the two works Mazda RX-7s and the lone NSX, which was also the first of the non-turbocharged cars.

However, late on Friday there were serious doubts that the NSX would take its place on the second row of the grid for Sunday’s 4.45am race start after Gardner lost control of the Japanese supercar at around 180km/h exiting McPhillamy Park during final practice and drilled the concrete wall at Skyline – hard.

The motorcycle ace emerged shaken but unhurt. The same could not be said for the NSX. However, the onsite TAFE Smash Repair Team under the supervision of Clive Weiss and Tony Warrener set about trying to resurrect the Japanese supercar in time for Sunday’s race, in what would be a marathon 36-hour repair job.

In a fascinating interview with AMC magazine in 2010, Warrener reflected on what he, without hesitation, claimed was the toughest repair job performed by his team of apprentices in its 25 years of operation at the Mountain.

“What made that job so hard was that the NSX was an all-aluminium car,” Warrener told AMC. “The chassis had a webbing in it which we didn’t know about. So as much as we pulled the rail, the webbing would pull it against us.”

Long-time TAFE SRT member and trade supplier Tony Doyle recalled that the Honda factory engineer Palmer hired for the race oversaw the repair at first, but when the initial chassis straightening attempts failed, declared the car unfixable.

“Tony (Warrener) double-checked with the Honda engineer that he was done,” Doyle explained. “Then he conversed with the car owner Ross Palmer and they decided they would have a shot at fixing it – Tony’s way.

“Then Tony, like an army general, bellowed out to everyone in the shed: ‘WE ARE GOING TO FIX THIS CAR – DO YOU UNDERSTAND!’ The apprentice crew, already dead on their feet from trying it ‘the Honda way’ and thinking they were beaten, sprang to life. It was like something you’d see in a military campaign.”

Warrener: “At one stage we actually had 30 tonnes of force pulling on it to bring the rail into line – three draw arms with 10 tonnes of force each. We had to cut the rail then cut the (internal) webbing to pull it into shape and then, under stress, re-weld it. We had 10 people working on that car non-stop for 15 hours, which equates to a month’s work in a regular workshop.”

According to a race report in Chevron Publishing’s Australian Motor Racing Year, the Smash Repair Team had been working non-stop on the NSX since Friday afternoon’s crash and on a bitterly cold Easter Sunday morning the exhausted but elated TAFE apprentices were still bolting it back together only 15 minutes before the 4.45am race start.

They did manage to complete it just in time for Ian Palmer to trundle down pit lane in the darkness and join the race as the leaders were approaching Hell Corner after completing their first lap, so the Honda was a lap behind from the start. However, the never-say-die spirit of the TAFE team was infectious and the Palmers, Gardner and the Honda pit crew tried to repay their faith with a similar approach to the race according to the AMRY report:

“The joker amongst the Porsches and Mazdas during the early running had been the Honda NSX, which circulated with the leaders throughout the early morning, if one lap down. Ian Palmer’s opening spell in the Honda had been excellent. He’d stepped into a car that had been hastily prepared but just went for it straight away. The repair job had been excellent, too, Palmer’s hot pace bearing testimony to that.

“Still, there hadn’t been time for all those ‘little things’ – in the darkness during the first hour or so Palmer could not find the electric controls for the mirror adjustments, and so until the sun came up the Queenslander had little idea of what was following the Honda.

“The Honda’s front-running pace quickly brought it through to a front-running position, if still a lap down, but the Dogbone car’s chances nose-dived early in the afternoon when the clutch springs failed. It would spend much of the rest of the race stuck in fourth gear, but even with that handicap the Palmers and Gardner were able to bring it home fifth on the road.”

A top-five result was fitting reward indeed for such an amazing fightback. However, the Honda team was soon elevated to third place and first in Class C (Touring Cars 2501-4000cc) behind the works RX-7s, after the Porsche 968CSs which finished second and third were excluded after post-race scrutineering checks revealed illegal wheel offsets.

One can only wonder what the NSX could have achieved at Bathurst without dropping a lap at the start and without the clutch problem that hampered its progress in the final hours of the race. Even so, it showed it could cut it with some of world’s finest high performance thoroughbreds in standard showroom trim, on one of the world’s toughest race tracks.

Just as its famous F1 test driver would have expected. After all, there’s a little bit of Ayrton Senna in every Honda NSX.