EH Holden S4: The General’s first ‘Bathurst Special’

The EH S4 entered by David McKay’s Scuderia Veloce for Brian Muir and Spencer Martin is captured at full speed across the top of the Mountain in the 1963 Armstrong 500. Note how physical Muir is getting with the steering wheel through McPhillamy Park, which in those days still had a monster gum tree sitting right on the apex.

The annual Bathurst 500/1000 has been the catalyst for some legendary Holdens built with race-winning specifications, but the first was a unique version of the EH sedan built for the inaugural ‘500’ held at Mount Panorama in 1963.

The EH S4 did not win in its first and only appearance in the Armstrong 500 but it did finish second, beaten only by a works-entered Ford Cortina GT which was also the first car to complete the 500-mile (800 km) distance at a time when outright winners were not formally acknowledged.

It was a gutsy effort by Holden to have a genuine - if largely clandestine - crack at winning the first Bathurst 500, at a time when GM was enforcing a strict global ban on factory participation in motor racing. If the bosses in Detroit discovered what their Aussie outpost was up to there would have been hell to pay, but Holden’s local chiefs considered the risk worthwhile.

Ford’s well-publicised victory in the 1962 Armstrong 500 at Phillip Island with the EJ Holden’s family car nemesis - the XL Falcon - sent shockwaves through GM-H and triggered a counter attack the following year with the EH S4. This is the ‘works’ Falcon (with 170cid Pursuit engine) on its way to that famous Island victory in 1962 driven by reigning champs Harry Firth and Bob Jane.

The problem for GM-H at the time, when it held a staggering 50 per cent of the new car market, was burgeoning rival Ford Australia’s enthusiastic involvement in motor sport. Unlike GM, Ford was in full support of this strategy to help rebuild the local Falcon’s reputation damaged by early durability issues.

The shock result that fired up a previously complacent Holden was the XL Falcon’s victory in the 1962 Armstrong 500 – the last to be held at Victoria’s crumbling Phillip Island circuit. The works-entered 170 Pursuit-powered Falcon shared by Harry Firth and Bob Jane was not only first across the line but also led home an emphatic 1-2-3-4 Falcon quartet in its class. A privately-entered EJ Holden finished fifth in class, seven laps behind the winner!

Also raising the stakes for The General was the Armstrong 500’s move from Phillip Island to Bathurst in 1963 under new race organiser the Australian Racing Drivers Club (ARDC). It was also to be the first live national telecast of the race by the Seven Network, so the threat of another potential Falcon victory under those circumstances was too dangerous to ignore.

Check out how hard the suspension is working on the Ralph Sach/Fred Morgan EH S4 as it sweeps through the daunting McPhillamy Park during the 1963 Armstrong 500. And how skinny were those tyres!

In those days, a manufacturer had to produce in series production at least 100 examples of a car they wished to race at Bathurst. This approval process known as ‘homologation’ ensured Holden was set on a path to creating its first Bathurst ‘homologation special’.

Its choice of weapon was the latest EH sedan, launched in August 1963 and just in time for the Armstrong 500 in October. Apart from its harder-edged styling, the biggest change over the previous EJ was a choice of all-new ‘Red’ six cylinder engines in 149cid (2.4 litre) and 179cid (2.9 litre) capacities, which offered far superior refinement and performance to the venerable ‘Grey’ sixes which had been powering Holdens since the first 48-215 in 1948.

In the 179's case, its 115bhp represented a staggering 53 per cent power increase over the EJ's relatively wheezy 138cid/75bhp Grey motor. However, the rest of the drivetrain and chassis hardware was basically carried over from the EJ and clearly stretched in dealing with the performance increases of the new red-coloured engines. The fact that the 179 engine was only offered with an automatic transmission at launch highlighted Holden’s concerns about drivetrain strength.

Even so, behind the scenes GM-H had been busy drafting the mechanical menu for its first Bathurst special – the S4 – which was the first EH to match the new 179 engine to the venerable three-speed column shift manual gearbox in production. However, there were numerous other differences between the S4 and the standard 179 Special sedan on which it was based:

An unusual shot of how the top of the Mountain looked during the first Armstrong 500 in 1963. The Harry Budd/Ron Smith EH S4 leads one of the Minis on the infamous roller coaster ride that scared the pants off many rookies and captured the public’s imagination.

Engine

S4 engines were all based on the standard 179 with a claimed 115bhp (86kW) at 4000rpm and 175 ft/lbs (236Nm) at 1600rpm. Some claim 120bhp. The main focus was on durability and minimising frictional losses, so Holden engineers hand-picked the best sets of components (cranks, rods, pistons etc) from the production lines and assembled each blueprinted and balanced S4 engine with great precision. The result was a noticeable improvement in refinement and throttle response with a freer-revving character. The jetting in the Stromberg single-choke downdraught carb was optimised and the 179 auto’s larger capacity radiator adopted to keep a lid on engine temps.

Clutch

A heavier duty clutch that was 0.5 inches (13mm) larger in diameter was specified to ensure it could handle the typical abuse experienced in competition use.

Gearbox

The EJ’s venerable three-speed manual gearbox with column-shift was beefed up to cope with the 179’s increased power and torque, with hardened gears and a new bell-housing design with a different bolt pattern to boost rigidity. This also required changes to the exhaust pipe shape and shift linkages for adequate clearance. The transmission assembly serial number included an S4 suffix.

Tail-shaft

More evidence of Holden’s concern about drivetrain strength could be seen in the 7mm increase in tail-shaft thickness over the standard EH.

Rear axle/final drive

To improve acceleration up the Mountain, a shorter 3.55:1 diff ratio replaced the standard model’s 3.36:1 ratio. The S4’s diff carrier was also cast with a high nodular iron content for greater strength.

The EH S4’s leaf-sprung live axle rear suspension was criticised for its marginal strength, axle tramp and a spooky ‘rear steer’ effect in fast corners caused by severe spring deflection. Here the Jim O’Shannesy/John Brindley S4 appears to be testing all of those traits as it chases the ill-fated David McKay/Greg Cusack Vauxhall Velox through Hell Corner at Bathurst in 1963.

Suspension

Basically standard EH, although the front cross-member also carried S4 identification. Cars that raced at Bathurst were allowed to run Armstrong’s latest sports shocks, but they struggled to tame some fierce axle tramp.

Brakes

A Repco-PBR brake booster increased pedal pressure on the rock-hard sintered metallic linings used at Bathurst, which only started to bite when they got really hot. Although some claim the S4s were fitted with these linings as standard equipment, others like former Scuderia Veloce mechanic Bob Atkin claim they were a race-only option. Brake shoe retaining springs were also improved.

Wheels

Standard EH (4.5 x 13-inch) but with stronger commercial vehicle-type riveted centres in place of the standard passenger car’s spot-welds (some still failed in the race though) and a different part number. Some claim the S4 wheels also had a 0.5-inch off-set to improve handling, but this is not mentioned in factory documents.

Tyres

Although the usual 6.40 x 13 cross-plies were supplied as standard equipment, Bathurst race rules mercifully allowed the use of radials. The Michelin X and Pirelli Cinturato were popular choices, along with Dunlop’s B7 and Goodyear’s Blue Streak.

Brian Muir pushes the stricken Scuderia Veloce S4 into pit lane after its tail-shaft broke during the 1963 Armstrong 500. At the front of the car is Muir’s young co-driver Spencer Martin, who had impressed SV team owner David McKay with his prodigious speed in a 48-215 that year. Martin was destined to become an open wheeler star and multiple Gold Star champion with McKay’s team.

Fuel tank

Exclusive to the S4 was a long-range tank which increased fuel capacity from the standard 9.5 gallons (43 litres) to 11.75 gallons (53 litres). It consisted of the top half of the standard tank mated to a new deeper bottom section, which hung down more noticeably beneath the boot floor. This ‘Bathurst tank’ concept would be copied in future race specials from Holden, Ford and Chrysler.

Tool Kit

The S4 was equipped with a comprehensive ‘Bathurst’ tool kit as the race rules at the time demanded that any repairs or servicing be done only with the tool kit supplied with the car. It comprised not only a jack and wheel brace but also a selection of pliers, screwdrivers and spanners, each with their own official part numbers.

Kerb weight

1120 kg

Performance

A spirited top speed of 105mph (170km/h) was claimed, thanks largely to the S4’s precision-built engine being able to spin freely to its 4000 rpm peak in top gear with the shorter 3.55:1 diff ratio. This far exceeded the top speed of the mainstream 179 Manual which followed early in 1964, which struggled to crack 90mph (144km/h). The S4 was also claimed to reach 60mph (100km/h) in 11 secs and cover the standing quarter in 19 seconds.

The first Armstrong 500 held at Bathurst in 1963 included a rule that all servicing and repairs had to be completed using only the car’s standard-issue took kit. The Muir/Martin S4 seen here lost any chance of winning while repairs were made to its rear suspension and tail-shaft. We think the bloke lying on the ground and wrestling with the good old scissor-lift jack is one of the drivers Brian Muir!

The Bathurst controversy

To comply with the ARDC’s 100-unit minimum production rule, Holden produced six S4s at its Dandenong plant in Melbourne and another 120 examples at its Pagewood plant in Sydney.

The Melbourne cars were mostly Winton Red with Fowlers Ivory roofs. Three were originally earmarked for Bathurst race duties in a star-studded team backed by Victorian Holden dealers, but that plan was abandoned. The Sydney cars were produced in different colours and had S4 build plate identification, but were otherwise identical to the Melbourne cars.

Founding Shannons Club contributor Joe Kenwright pieced together a very detailed EH S4 profile for AMC magazine in 2003, in which he outlined what happened to the six Dandenong cars:

“Few of the Melbourne S4 examples reached Bathurst. Number 305 went to the police for evaluation. Number 300 – which was originally red and white – became Norm Beechey’s famous Neptune racer. Numbers 301 to 303 were to be the three Melbourne dealer race cars. Of these, one was believed to have gone to motor sport identity Lou Molina, one to the police and another became the Scuderia Veloce entry driven by Spencer Martin/Brian Muir. Number 304 went to Rom Beith, possibly as a reserve Scuderia Veloce car, but Ron died before he could race it.”

The Ian Grant/Trevor Marden S4 has its rear-view mirror filled by the Kevin Bartlett/Bill Reynolds S4 as they belt through McPhillamy Park during the 1963 Armstrong 500. This was future winner Bartlett’s Bathurst 500 debut, but it was not a happy one as the car showed a nasty tendency to break wheels.

Although GM-H had built more than enough S4 examples to meet the 100-minimum rule for the 1963 race, it also had the unenviable task of distributing them across a national network of 600 dealers. As a result, a few privileged dealers got S4s but most missed out.

This quickly started alarm bells ringing about its legitimacy. Why couldn’t you buy an S4 from any local Holden dealer? Why did Holden dealers claim they knew nothing about the car? Did GM-H really build 100 examples? Why were there no official price list or workshop manual issued for the S4 as required by the race rules?

In its October 1963 issue, Racing Car News magazine published an excellent editorial about the S4 Bathurst controversy, which explained how Holden’s quick-thinking solved the problem:

“A couple of weeks prior to the closing date of entries for the Armstrong 500 race, news filtered through to Sydney of a special Holden. Called the EH S4, this Holden was reputed to sell for under 1200 pounds (the limit for Class C at Bathurst) and was reported to be much faster than the normal range of cars which were available only with the small motor (149cid) in the manual transmission car, or the big motor (179cid) with automatic transmission. The S4 had the big motor and the manual box and a team entry was expected from the Victorian Holden Dealers.

“Enthusiasts in Sydney immediately tried to buy an S4 with varying results. Some were able to purchase cars at 1160 pounds, one dealer offered the S4 only with 200 pounds worth of optional extras which took it out of Class C, some dealers said they had never heard of the S4 despite the fact they had registered S4s in the back room. Lots of tempers were frayed.

“About a week before entries closed the first S4 entry was received by the Armstrong organisers who discovered a few problems. Firstly, they could not obtain a printed ‘Price List’ from the dealers, who referred them to GM-H. GM-H would not furnish a price list either, which meant the ARDC left themselves (sic) open to protest should the S4 win its class.

“Secondly, no workshop manual was available so the organisers had no data from which their scrutineers could work. Therefore it was announced that the S4 could not be accepted, resulting in a lot of ill-informed criticism and different sets of tempers being frayed.

The O’Shannesy/Brindley and Muir/Martin S4s lead one of the Minis down through the Dipper during the ’63 race. Look at the fully extended front coil spring on the Muir/Martin car, as the road suddenly drops away from under the tyre. Note also the standard vinyl seats and lack of roll bars in those days.

“The day before entries closed, GM-H furnished the necessary price list and furnished a workshop manual listing the S4. The organisers then announced that the S4 would be acceptable.

“It was immediately assumed by a lot of people that GM-H had deliberately engineered this confusion in the hope that the Victorian Dealers Team of three cars would not have a lot of S4 opposition from independent drivers. But the strange thing was that when the closing date came around, no entry was received from the Victorian Dealers Team, their cars having been handed over to the police for testing.

“For many years, the sport has been anxious to see GM-H taking an active part in competition and it appears fairly obvious that the S4 was produced principally for the Armstrong 500. It is a great pity that this situation should have occurred, but the organisers acted in the best interests of all by insisting that the S4 entry complied with printed regulations for the event and no blame for the resulting confusion can be laid at their doorstep.”

It should also be pointed out that development of the S4 was money well spent by Holden, because many of the components developed for the car ended up being adopted by the mainstream EH 179 Manual model launched in February 1964. By which time the controversial S4 was dead and buried (as a Bathurst contender at least) as far as The General was concerned.

The Muir/Martin S4 powering through Griffin’s Bend as it climbs the Mountain during the 1963 Armstrong 500, ahead of the Vauxhall Velox shared by Scuderia Veloce team-mates David McKay and Greg Cusack. The British car lasted only 20 laps before retiring with engine damage.

The Race

GM-H would have had good reason to think its 179cid, three-speed manual, drum-braked EH S4 family sedan would at Bathurst confront Ford’s reigning Armstrong 500 champion – the 170cid Pursuit-powered XL Falcon, also with three-speed manual gearbox and drum brakes. On paper the S4 would have more than held its own.

However, behind the scenes a decision to stop racing the Falcon had been made following its victory in the 1962 Armstrong 500 at Phillip Island, as Ford’s contracted car tweaker/driver Harry Firth plotted the company’s competition future:

“After the ’62 Armstrong 500 I said to Ford, ‘listen, the Falcon as it is now is a dead duck,’” he wrote in his Ford memoirs for Chevron Publishing. ‘You’re not going to win anything more; there’s no way you’re going to win the race at Bathurst next year with it. I’m not driving one of these things any more when you’ve got a perfectly good and suitable car sitting there in the Cortina. It’ll walk Bathurst in!’”

Ford took Firth’s advice and promptly nominated the new 1.5 litre four cylinder Cortina GT as its main strike weapon for the first Bathurst 500. However, this was no ordinary Cortina GT. Firth, nicknamed ‘The Fox’ due to his cunning approach, had also devised what was effectively Ford’s first ‘Bathurst Special’:

“I was able to persuade the management of Ford Australia to import one hundred kits of the new Cortina GT complete with low European springs. By building the vehicles in Australia, we could delete all sound-deadening material and provide minimal paint cover. By accurately controlling the manufacturing process, we could ensure we got a body shell built to sufficient strength for racing through adequate spot-welding. The final outcome would be a vehicle of considerably reduced weight.”

Harry Firth is a study in concentration as he pilots the 1963 Armstrong 500-winning Cortina GT through Murray’s Corner. His success in convincing Ford to switch from the XL Falcon to the hottest version of the new UK Cortina proved to be a winning strategy, as the S4 was outfoxed by a superior car and race plan.

Ford’s ‘Bathurst’ Cortina GT was not only smaller and more agile than the S4; it was also about 300 kg lighter (a massive advantage) and equipped with superior front disc brakes. Those attributes, combined with the Cortina’s better fuel economy and smaller appetite for tyres and brakes, added up to a far superior Bathurst contender than the Falcon. Put simply, Holden had been outfoxed by ‘The Fox’ himself!

The 1963 Armstrong 500 field was broken up into four classes based on retail prices, with Class C (£1001-£1199) attracting four Cortina GTs, six EH S4s and a lone FB Holden. Class C was also expected to produce the first unofficial outright Bathurst winner, which despite being ignored by race organisers was of immense importance to everyone else.

The Ford attack was led by works entries for reigning Armstrong champs Firth/Jane and the Geoghegan brothers, Leo and Pete. The six EH S4s were all dealer-entered (as per GM’s racing ban) and attracted a variety of driver pairings, with the strongest performance expected to come from David McKay’s Scuderia Veloce entry shared by the very quick Brian ‘Yogi’ Muir and Spencer Martin.

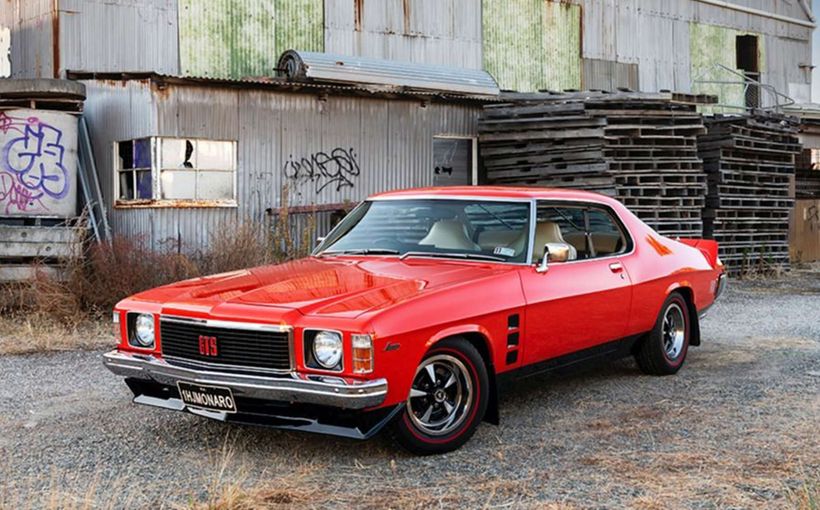

The EH S4 proved to be a potent racer under the Appendix J touring car rules of the early 1960s, which allowed for modifications to improve performance. Here Brian ‘Yogi’ Muir in his Waggott-developed S4 is leading Stormin’ Norm Beechey in his famous Neptune Racing Team example at Queensland’s Lakeside Raceway in 1964. Muir and Beechey were the S4 ‘big guns’ of the era.

As it turned out, the S4s suffered a variety of mechanical problems and racing mishaps which ensured they never troubled the Firth/Jane Cortina GT, which enjoyed a faultless run and a runaway victory in Class C. It was also the first car to complete the 130-lap distance.

Ralph Sach/Fred Morgan were in the highest placed S4, finishing second in Class C (and second overall) but more than a full lap behind the winning Cortina following a long stop for repairs after being rammed in the tail.

The Harry Budd/Ron Smith S4 was next best, fifth in class and seven laps behind the winner. The Ian Grant/Trevor Marden S4 claimed sixth in class a further three laps adrift, ahead of the troubled Kevin Bartlett/Bill Reynolds S4 in seventh and 15 laps down after suffering two broken wheels.

Brian Muir’s EH S4 leading Pete Geoghegan’s Cortina GT during a torrid dice at Sydney’s Warwick Farm Raceway in 1964. Under the Appendix J rules, touring cars like Muir’s S4 pushed the limits on modifications, particularly engines. Note how much lower his car is compared to the standard Bathurst cars in previous shots. Those wheels and tyres still look awfully skinny though - and so does the steering wheel!

The highly fancied Scuderia Veloce S4 of Spencer Martin/Brian Muir finished next to nowhere, after a centre bolt broke in one of its tortured rear leaf springs and allowed the spring to move back far enough to snap the tail-shaft. They lost about 19 laps in the pits repairing the damage, using only the car’s standard-issue tool kit!

The last of the six S4s shared by Jim O’Shannesy/John Brindley was out after 65 laps when O’Shannesy rolled it approaching the Dipper. For the record, the lone Grey-engined FB did better than both of them, cruising along to eighth in class 15 laps behind the winner.

The exuberant Norm Beechey and his famous Neptune Racing Team EH S4 in a full-blooded power slide at Sydney’s Warwick Farm in 1964. Beechey’s home-grown hot-rodding skills saw him squeeze massive power from the 179 straight six. Bored-out to just under 3.5 litres, with triple side-draught Webers and the best internals, ‘PK-751’ was claimed to produce a whopping 232bhp (more than double the standard output) at a spine-tingling 7500-7700rpm. When the rules changed for 1965, Norm moved to a new V8 Ford Mustang.

“The S4 could have and should have won,” he said. “For its day, the handling and performance were very good. There was a lot of body roll – which was typical of the era – but the car was very predictable. It was the usual business of understeer going into a corner then putting in the boot to get the tail out on the way out."

However, his Scuderia Veloce chief mechanic Bob Atkin disagreed. “They were too new,” he said. “Nobody had enough experience with them and you couldn’t really expect to beat a proven car like the Cortina GT without a lot of testing.”