Datsun 180B and 180B SSS: 1600 lingers on beneath embellishments

The Datsun 180B more than just about any other car I can think of exemplifies the automotive trends of the 1970s. This successor to the remarkable Datsun 1600 represented an attempt by Nissan’s product planners to build on a winning formula. But in many ways, the result was a classic case of half a step forwards, one step backwards.

In the 1970s, it was often the case that brave engineering solutions from the previous decade were abandoned. The Fiat 131 had disc brakes up front and drums on the rear, while its brilliant 124 predecessor had discs at each corner. The Rover SD1 lost the P6’s sophisticated De Dion rear end with in-board rear discs in favour of a simpler Watts Link arrangement with drum brakes. To their credit, Nissan persisted with the 1600’s independent rear suspension.

Nevertheless, where the 1600 looked like a brilliant piece of design beautifully executed, the 180B appeared to be fussier and compromised in more areas.

The 180B was curvy where the 1600 had been hard-edged. It was also heavier and much more highly embellished. Despite an increase in engine capacity from 1.6 litres to 1.8, the overall performance was only minimally improved while economy, at best, was unchanged.

In that era when only luxury cars – and not all of them – were equipped with power steering, the 180B’s extra weight meant increased effort was required for parking. The February 1973 edition of Modern MOTOR includes this telling observation:

Datsun has stuck with recirculating ball steering – and it’s a sensible choice. The steering is still light (though one staff member who’d had considerable experience with the Datsun 1600 complained it was heavier when parking).

A few paragraphs later we find this overview of the 180B’s suspension:

Nissan’s rework on the Datsun is most complete, but I feel the suspension department was neglected. Certainly, wheelbase was stretched three inches on a new floorpan and the tracks were bumped out a couple of inches to give a wider stance and firmer grip.

But the basic suspension system was maintained exactly as per the Datsun 1600 with only minor adjustments to spring and damper rates, and geometry.

The result is that neither ride nor handling have been improved noticeably. Certainly the improvement in handling is far below what I would have expected – and it’s nowhere near the improvement seen in its leading opposition, the Cortina.

The car still feels narrow and long. Pushed into a corner, it understeers firmly and the steering loads up progressively. It doesn’t plough viciously and the condition is most stable, but the transition to oversteer when the power is cut is slower than on the Datsun 1600 and the chuck-about-ability seems reduced…

The overall trend in the car’s suspension is towards a boulevarde ride, and the average motorists will definitely welcome this.

That last paragraph holds the key to the 180B. Although it was to incorporate key engineering elements of the 1600, it was aimed more at the undiscerning driver, at the expense of the enthusiast. Sad to say, this seemed to be the way of the 1970s (sometimes dubbed ‘the decade that good taste forgot’).

Most testers commented on the vagueness of the steering, a point rarely raised in commentary on the 1600.

This revision of what had been a great design reminds me of what happened at Fiat in the same time frame. The 132 which replaced the hard-edged and highly effective 125 came into the same category as the 180B. History has spoken quite clearly on both cars: the Datsun 1600 and Fiat 125 will always be regarded as classics – among the best mainstream models produced anywhere in the world in the second half of the 1960s, but the 180B and the 132 (particularly) are also-rans.

It was a time when cars were designed to appeal internationally and in essence this meant a loss of character in many cases. The Fiats 132 and 131 replacing the 125 and 124 respectively are perhaps the clearest examples. The mainstream nature of the Renault R12 compared with the R16 of a few years earlier is another. Even the Citroën CX was less radically French in flavour than its illustrious Diesse predecessor.

At least, I can report that the 180B was less of a failure of courage than the designed-by-a-dull-committee 132. Road testers of the time tried hard to fall in love with the 180B but the car usually seemed to let them down in quite small ways. In at least two contemporaneous Australian road tests, the handling was compromised by inferior tyres.

The 180B sedan and wagon were assembled in Australia, while the SSS coupe was fully imported.

All versions of the 180B were more accelerative than their rivals and it was only the relative lack of advancement over the 1600 that caused the raising of eyebrows.

The single overhead camshaft engine that was so integral to the 1600’s appeal was actually designed by Prince (which merged with Nissan in 1966). It was noisy beyond 6000rpm but it’s worth remembering that few production car engines of the era could even aspire to such heights.

But if buyers of the 180B would have welcomed the boulevarde ride, few would have enjoyed such a raucous engine. At least with its strong torque, the 180B did not need to be revved hard to perform well. With its 10 additional horsepower, thanks to a higher compression ratio (9.5:1 versus 8.5:1) and the use of twin Aisan carburettors rather than the cooking variants’ single dual-throat unit, the SSS hardtop was even noisier when fully extended. It could be revved safely to 7000, although there was no point in exceeding 6000 (except perhaps for brief moments on a track day).

Peak torque was developed at higher rpm, but a high final-drive ratio enabled the car to cruise effortlessly at high speed.

The SSS was better equipped than the locally assembled 180B variants, although its seats were less comfortable. It came with a tachometer, laminated windscreen, heated rear window, anti-glare mirror and radials as standard. The use of gas-filled rear dampers enabled the independent rear suspension to work more effectively in the SSS. It also had a proportioning valve for better regulated braking.

Because the SSS was subject to a 45 per cent tariff regime, this was a much more expensive alternative, priced at $3395. The cheapest 180B sedan cost $2570 (and $2820 with the three-speed automatic transmission). The popular GL manual cost $2690 and the auto version was $2940.

Its rearward visibility was even worse than the sedan’s but there was something of a trade-off in the cocooned, sporty feel of the interior and the consolation of a 7000rpm tachometer. Perhaps the real pity is that the engine had not been coaxed to yield more like 125 horsepower and equipped with a five-speed gearbox.

The SSS competed directly with the Toyota Celica and peripherally with the Fiat 128 coupe.

Naturally, the SSS sold in low volumes. By contrast, the sedans and wagons were very popular. Well before the end of its sales run, the 180B was being seen by many as foreshadowing the new type of Australian car. Wheels ran a cover story: ‘Australia’s Own: will it be Datsun 200B?’ for its October 1975 edition. Steve Cropley compared a locally assembled 180B with the HJ Kingswood Deluxe, finding in favour of the latter for its higher standard of finish and stronger construction.

Even though sales of four-cylinder Japanese cars were burgeoning, there was still a strong case to be made for Kingswood, Falcon and Valiant. Fleet operators found literally to their cost that giving sales reps Datsun 200Bs or Sigmas to drive instead was a false economy. The Mitsubishi Magna – a brilliant concept (though let down by assorted issues until the TP of 1989 – was still almost eight years into the future when the 200B replaced the 180B. Japanese cars were narrow and felt somewhat cramped when asked to carry an Australian family with teenage children.

Remarkably, although the 180B was almost six inches longer than the 1600, there is little evidence of a significant gain in spaciousness or boot volume.

According to Modern MOTOR:

The car looks bigger but is not obviously bulkier to drive – except when parking. Even then, the size increase is not noticeable so much for its overall dimensions, bur rather in terms of visibility – the cleaner. Squarer lines of the superseded car facilitated parking, whereas the 180B has a heavy taper to the rear panelwork, and a very serious blind spot in the thick rear quarter panel (or C-pillar) and a low seating position which further reduces visibility.

However, in terms of general roadability, the car feels dimensionally similar to its predecessor, and most drivers will be unaware of an increase in bulk.

There is no mention of greatly increased interior room, while the boot is roundly criticised:

The boot is another area that has suffered at the hands of styling. It is down on usable space and has a small high-lipped aperture.

To be fair, the 180B was about average in these respects. Real space efficiency in cars was generally evident only in European models such as the Peugeot 504 and Citroën CX. Japanese cars were restricted by a maximum width decree.

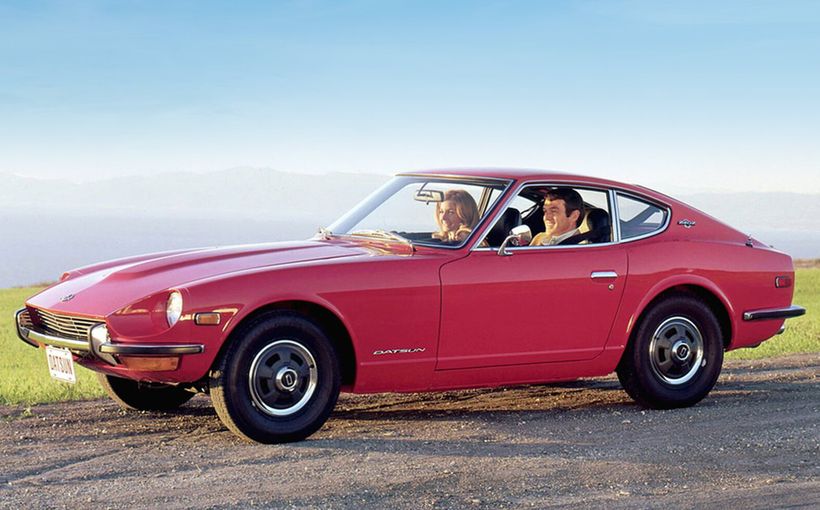

In summary, the Datsun 180B was a typical 1970s Japanese model, enlivened by a touch of Prince. It was unashamedly pitched at the average buyer with little interest in the finer points of driving. Despite being bigger than the charismatic Datsun 1600, it offered few tangible gains in accommodation while sacrificing much of that car’s spunky character. But it tended to win multi-car comparisons with vehicles such as the Corona and Mazda Capella. And the Datsun 180B did offer the strongest performance in the class, thanks to its lusty engine which had been designed by Prince. It is even possible to argue that it has been Nissan’s takeover of Prince that has permitted the company to build its best models, including such cars as the Datsun 240K and 240Z and the stupendous Nissan GT-R.

With Nissan Australia’s local assembly stretched to the limits, the company did import a few 180B GX sedans from Japan. They were nothing to write home about, even though the option of air-conditioning was appreciated. When it came to the cooking 180Bs, the local versions were just as good as the imported.

For enthusiasts though it is indeed an imported 180B that will always exert the greatest appeal – the SSS Hardtop. With its coupe bodywork, extra features, superior high-end performance and relative rarity, the 180B SSS was one of the better offerings of the 1970s.