Volvo 850: The Estate Car Turned Racing Superstar!

Volvo has scored some big wins in international motor sport, from the East African Safari in the 1960s to the European and Australian Touring Car Championships in the 1980s. And another of its greatest motor sport achievements occurred in the 1990s – without even winning a race.

Its boxy 850 Estate (aka station wagon) competed for only one season in the world-famous British Touring Car Championship in 1994 and for another season in the Australia Super Touring Championship. And during that time the 850 Estate never took pole position or won a race, a round or a championship.

Volvo wasn’t disappointed with the results, though. Its primary goal at the time was to let the world know that the Swedish car maker still had a pulse, as its victory in the 1985 ETCC with the 240 Turbo was by then a distant memory. To attract a younger and more ‘hip’ buyer, Volvo was again embracing the excitement of motor sport to drive that message home.

And in that sense, the decision to race its big boxy 850 Estate was a marketing masterstroke. Even though the cars didn’t win they became instant favourites with race fans and hogged a sizeable amount of airtime during slickly-edited BTCC race highlight packages, which pulled huge TV ratings around the globe.

And in those pre-internet days, the 850 Estate race car was also a catalyst for countless feature stories published in the motor sport press, daily metro papers and much further afield in glossy publications which would not normally feature automotive stories.

The end result was a most unlikely race car that became an international superstar, earning Volvo arguably millions of dollars’ worth of free publicity while also serving as a valuable test and development mule for the more successful 850 sedan race cars that followed.

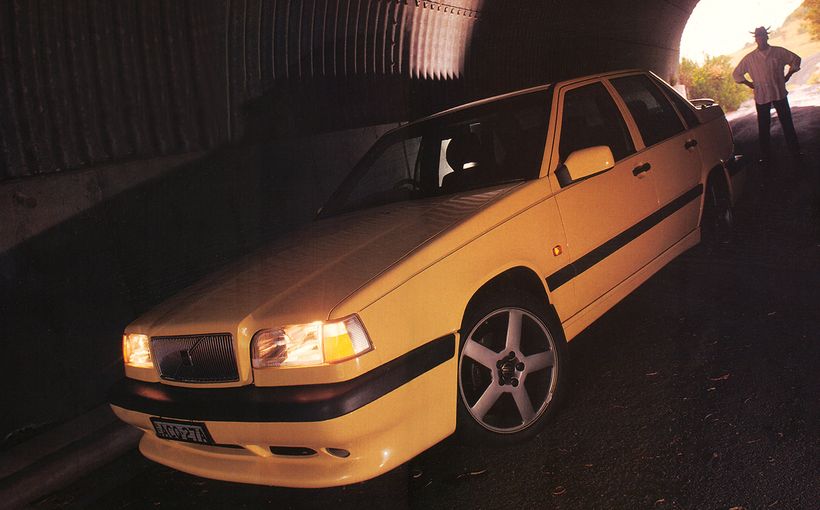

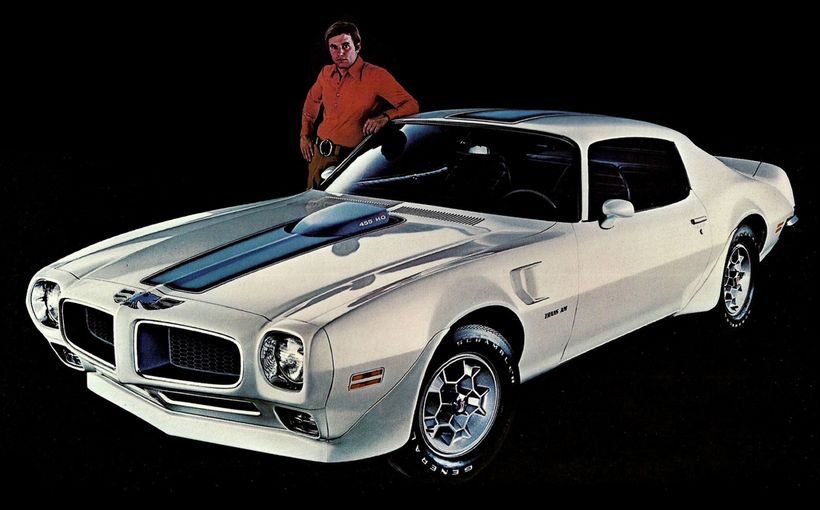

Dutch F1 and Le Mans-winning sports car driver Jan Lammers teamed with Sweden’s Richard Rydell for Volvo’s high profile entry to the 1994 BTCC in a pair of 850 Estates designed and built by TWR. In a season dominated by Alfa Romeo’s 155 sedan Volvo got right into the spirit of the Estate lifestyle, even mounting a stuffed border collie in the rear of the wagon (and sometimes on the roof) during parade laps! Image: www.pinterest.com

From Concept to Reality

Volvo’s bold decision to race the Estate, a model available in the new front-wheel-drive 850 range released in 1991, was triggered by a twist of fate which would play a pivotal role in motor sport history.

According to reports at the time, company boss Martin Rybeck had commissioned Sweden’s Steffansson Automotive (SAM) to design and build a racing prototype of its new 850 sedan to suit the FIA’s blossoming 2.0 litre Super Touring class.

When SAM staff arrived at the plant to collect an 850 engine and body shell there were no sedan shells available, but as the project was to proceed without delay SAM had no choice but to use the Estate body instead. However, when Rybeck found out about it, he could see huge marketing potential in actually racing the Estate and instructed SAM engineers to proceed on that basis.

The next stage in the process was testing of the sedan and wagon bodies in a wind tunnel to determine if there were any major differences in aerodynamics that would negatively affect the 850 Estate in competition. Surprisingly perhaps, the tests showed little difference between the two and if anything the Estate was slightly better.

TWR squeezed plenty of power from Volvo’s 2.0 litre DOHC 20-valve inline five cylinder engine. Being mounted transversely or ‘east-west’ in the 850’s spacious engine bay allowed it to be located well back for better chassis balance. Note the toothed rubber belt that provided drive for the twin overhead camshafts and engine ancillaries. Image: www.pistonheads.com

Volvo’s enthusiasm was given another boost after initials talks with Tom Walkinshaw Racing about the Estate’s potential as a Super Tourer. TWR engineers confirmed that even though the wagon body would naturally carry more weight behind the rear wheels and have a slightly higher centre of gravity than the sedan, there would be a negligible difference in overall performance provided the wagon’s extra weight could be trimmed to meet the class minimum.

Volvo soon announced that it would be entering the flourishing BTCC in 1994, having signed a three-year contract with TWR to design and build race cars based on its latest 850 series.

The 850 Estate race car was designed by TWR’s Richard Owen who had also penned Jaguar’s stunning XJ220. The boxy bodyshell was heavily reinforced with a welded tubular steel roll cage featuring plenty if triangulation for maximum chassis rigidity and driver crash safety.

The heart of the beast was the marque's howling 2.0 litre DOHC 20-valve inline five cylinder engine. In full race trim it was rated at a class competitive 280-290bhp at a screaming 8500rpm. Engine cooling was via a high efficiency single-pass aluminium radiator, with separate radiator coolers for engine and transmission oils.

Tony Scott in the factory-backed 850 GLT found life tough in the 1994 Australian Production Car Championship, beaten by smaller and faster Nissan Pulsar SSS rivals which finished first and second in the title race.

Power reached the front wheels through an X-Trac six-speed sequential gearbox, built to meet a specific TWR design brief which allowed the transverse-mounted engine to be lowered and moved back in the engine bay so that it sat wholly behind the front axle line.

This ‘mid-engine’ layout was only made possible by the extra room Volvo allowed in the engine bay for turbocharger installations on premium performance models like the 850 T-5. Getting the engine this far back greatly improved front/rear weight distribution and by moving such a heavy item as close as possible to the car’s centre of gravity (or axis of rotation) it also reduced the wagon’s polar moment of inertia, to sharpen its response to fast directional changes.

Positioning the driver lower, further back and more inboard than standard, using an extended pedal box and steering column, added to this low-polar effect while further improving driver safety. A Momo steering wheel controlled a TWR power-assisted rack and pinion assembly

Suspension comprised TWR front struts, a TWR racing version of Volvo’s new ‘Delta Link’ semi trailing arm/rigid beam rear suspension and Ohlins dampers all round. Hidden within its huge 18-inch diameter wheels and sticky race tyres were powerful Brembo multi-pot calipers and ventilated disc rotors at each corner. No doubt about it – this was a seriously high performance station wagon that would make any border collie car sick!

This is the very quick but ill-fated Volvo 850 T-5 shared by Tony Scott and Peter Brock in the 1994 James Hardie 12 Hour production car race at Mount Panorama.

1994-1996: The British Connection

Such an audacious decision by such a conservative company had the desired effect of jolting the public out of its sleepy perception of the marque. And any lingering doubts about Volvo’s commitment to success were erased with the announcement of a two-car team, with Swedish ace Rickard Rydell and Dutch F1 star Jan Lammers as drivers.

The two 850 Estates were only finished just in time to make the grid for the first round of the 1994 BTCC. At the end of the season, their combined best qualifying effort was third and best race result was fifth, with Volvo finishing sixth in the Manufacturers’ Championship.

Although the 850 Estates were clearly crowd favourites, Rydell and Lammers (who finished 14th and 15th in the driver’s title) didn’t share the same affection for them. The major drawbacks were that they were the largest and therefore most cumbersome cars in the field. And they had struggled for traction in slow corners, caused primarily by the wagon’s more rearward weight bias and corresponding lack of weight over the front wheels.

This traction issue was addressed by TWR in the 850 sedans that followed in 1995, but only Rydell chose to stick around. Lammers clearly didn’t enjoy the experience and abandoned the BTCC after one season, claiming that there was too little difference between his race car and the 850 Estate he drove on the road. Ouch!

Much was expected of Volvo’s upgraded T-5R in the 1995 Eastern Creek 12 Hour, but both works entries were plagued by numerous technical problems in the race.

Rule changes for the 1995 BTCC allowed the use of front and rear spoilers. They were clearly designed to favour sedans, as the rear spoiler was not allowed to overhang further than the rear bumper or be higher than the roof line. Any plans Volvo and TWR may have had to continue racing the Estate were effectively killed off by the rule makers.

The switch to the 850 sedan was more evolution than revolution, as the 850 Estate had pinpointed areas that needed improvement. Rydell and new team-mate Tim Harvey enjoyed a big boost in competitiveness, with Rydell emerging as a serious BTCC contender in 1995 with numerous pole positions, four race wins and third place in the championship backed by Harvey’s fifth place from two race wins and several podiums. Volvo also finished third in the Manufacturer’s points.

The 850’s third and final BTCC season saw Rydell outshine new teammate Kelvin Burt, taking five pole positions, four race wins and numerous podiums to again finish third in both the driver and manufacturer battles.

Although it was the end of the road for the big 850 in the BTCC, Volvo’s best was yet to come as it switched to the smaller and much sleeker S40 in 1997 which allowed Rydell to finally win the BTCC for TWR/Volvo in 1998.

The 850 Estates were often shunted from behind in their first and only BTCC season, as frustrated rivals complained of missing their braking markers because the Volvo's tall tailgate and big roof pillars blocked their forward vision! Here Tony Scott displays the 850 Estate’s substantial rear end at Oran Park in 1995.

1994-1997: The Australian Connection

Volvo’s return to motor sport with the 850 Estate in the BTCC was part of a global strategy, as Volvo Australia also provided its first factory support for a local motor sport program since claiming the 1986 Australian Touring Car Championship with the 240 Turbo.

To ease back into the sport after almost a decade’s absence, the Swedish car maker commissioned renowned race/rally car preparer and strategist George Shepheard to prepare an 850 GLT sedan for Queenslander Tony Scott to drive in the 1994 Australian Production Car Championship.

After several years of Falcon vs Commodore six cylinder warfare, new rules had been introduced for the 1994 APCC which restricted entry to road cars with engine capacities no greater than 2.5 litres and front wheel drive.

Rickard Rydell was highly competitive in the BTCC after Volvo switched from the 850 Estate to the sedan for the 1995-96 seasons. Here the Swedish ace shows his attacking style, taking flight at Brands Hatch on his way to third place in the 1996 BTCC. Image: www.en.wikipedia.org

The relatively large Volvo, with its 2.5 litre 20-valve engine, had its work cut out trying to topple the smaller and lighter Nissan Pulsar SSS which had strength in numbers and driver quality. The Nissans finished first and second in the championship ahead of Scott in third.

Although 1994 was the first and only time Volvo would compete in the APCC, it embraced the challenge of the annual James Hardie 12 Hour production car race at Bathurst that year by backing a works-entered 850 T-5 sedan for Scott and nine-time Bathurst 500/1000 winner Peter Brock.

The T-5 was a hotter and faster variant of the 850 sedan; its front wheels driven by a turbocharged version of the transverse five cylinder with more than 225bhp (168kW) on tap and a top speed on Conrod Straight exceeding 140mph (230km/h).

Nine-time Bathurst winner Peter Brock got Holden and HRT offside by racing Volvo’s ex-BTCC 850 Super Tourer in the 1996 Australian Super Touring Championship.

The T-5 performed superbly for more than 11 of the race’s 12 hours. Brock and Scott not only built a massive two-lap lead in Class T (Turbo) but were also running fifth outright, with only serious sports cars like the dominant twin-turbo Mazda RX7 and Porsche 968CS ahead of them.

However, with less than 40 minutes to go the T-5 was forced out with transmission failure. Volvo deserved much better after such a great performance. Volvo's pain was Subaru's gain as the all-wheel drive Impreza WRX shared by John Bourke/Mathew Martin/Wayne Park moved up to claim the Class T win and seventh outright.

Even so, Volvo was thrilled to have Bathurst and ATCC legend Peter Brock driving its cars because of the increased publicity and goodwill it brought to the Swedish marque. It was a relationship Volvo wanted to strengthen and hopefully exploit in future seasons.

1995

There were three 850 Estate works cars built for the 1994 BTCC in 1994. Volvo Australia caused a stir when it announced that one of those cars would take on the factory-backed BMW (318i) and Audi (80 Quattro) teams in the burgeoning Australian 2.0L Super Touring Championship in 1995.

However, if ASTC organisers had been expecting a close fight between the dominant German marques and the Swedish import, they were to be disappointed. The 850 Estate driven by Tony Scott struggled with similar performance issues experienced in the BTCC and was never a title contender. It finished eighth overall with a best race result of third place in the final round. The car was returned to Sweden at the end of the season.

The annual 12 Hour production car race was still considered a major prize worth pursuing, even though the race had lost its James Hardie sponsorship and moved from its original home at Bathurst’s Mount Panorama to Sydney’s Eastern Creek.

After such a stellar performance by the T-5 at Bathurst the previous year, Volvo was confident that its even hotter turbocharged T-5R could surpass it with two cars entered for Peter Brock/Tony Scott and another for UK touring car star Win Percy and local rally ace Ed Ordynski.

Despite solid pre-race preparations the Volvos were progressively crippled by brake, intercooler, wheel bearing, power steering and drivetrain problems, with the Brock/Scott T-5R struggling home to be the last classified finisher in 16th place while Percy/Ordynski joined the long list of non-finishers.

Jim Richards proved to be an ideal replacement for Brock in the works 850 Super Tourer in 1997. Although the ASTC crown still proved elusive for Volvo, Richards scored several top three placings to finish fifth overall in the driver’s title behind the factory BMWs and Audis.

1996

Volvo Australia caused another sensation in 1996 when it announced that Peter Brock would be stepping up from his previous production car duties to pilot an ex-BTCC Volvo 850 sedan in the Australian Super Touring Championship.

Brock also had a non-exclusive contract to drive a Commodore V8 Supercar for the factory-backed Holden Racing Team, but his signing of a new deal with Volvo to not only race its cars but also promote its road cars went down like a lead balloon with Holden and HRT.

Although much was expected of the new Brock/Volvo partnership in the ASTC, it was no match for the works BMW (318i) and Audi (A4 Quattro) teams which continued to dominate. Brock did not score a pole position nor race win on his way to a disappointing sixth place in the championship.

Given the chilly response from Holden/HRT, Brock announced that he would not be renewing his Volvo contract in 1997 but Volvo found an excellent replacement in multiple Bathurst and ATCC champion Jim Richards, who immediately claimed two second places and a breakthrough win in a trio of Super Tourer support races at the 1996 Bathurst 1000.

Richards and Rydell were outclassed at the 1997 AMP Bathurst 1000 for Super Tourers, but the best was just ahead for both drivers in 1998 with the smaller, sleeker and faster S40 model.

1997

Despite ongoing local development, the 850 Super Tourer could still not bridge the gap to the BMW 320i and Audi A4 Quattro. Like Brock, Richards also failed to score an ASTC race win on his way to a solid fifth place in the championship and a third for Volvo in the Manufacturer’s points behind Audi and championship winner BMW.

Proof that the 850 sedan (which by then had been replaced by the smaller and sleeker S40 in the BTCC) was past its prime was evident at the AMP Bathurst 1000, which in 1997 was exclusive to 2.0L Super Touring cars as the V8 Supercars moved to a separate event.

Volvo geared up for the new look race with a two-car team. However, despite the combined driving talents of Jim Richards and BTCC top gun Rickard Rydell in the lead car, they finished in fourth place a full two laps behind the winning BMW 320i. The second 850 shared by Jan Nilsson/Cameron McLean finished fifth and three laps behind the winner.

End of the road for the 850. The second works Volvo shared by Jan Nilsson and local driver Cameron McLean heading for fifth place at the 1997 AMP Bathurst 1000.

Richards updated to the latest S40 model in1998, as Rydell had done the previous year in the BTCC. It proved to be a winning move for TWR/Volvo on both sides of the globe, with Rydell finally claiming the BTCC crown which had eluded the 850 while Richards returned to the Mountain to claim the Bathurst 1000 win which was also beyond his 850 the previous year.

When measured purely by pole positions, race wins, points and championships, the 850 will not be remembered as one of Volvo’s most successful race cars. However, thanks largely to the 850 Estate, it proved a runaway winner in letting the world know that Volvo was getting an image make-over through racing. The 850 sedan which followed also showed that the Swedes were very serious about winning races and laid the foundation for their future BTCC and Bathurst victories with the S40.