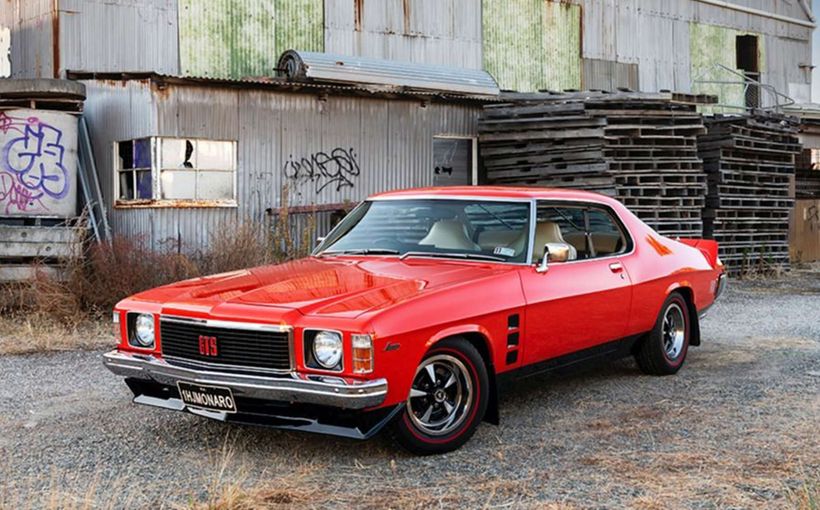

V2 Monaro: The Rise and Fall of Holden’s 7.0 litre V8 Super Coupe

Holden's bittersweet experiment with a 7.0 litre (427cid) V8 racing version of its V2 Monaro early in the new millennium – the Monaro 427C - was as successful as it was controversial. It dominated both of the Bathurst 24 Hour races, yet in doing so attracted criticism from rivals and fans.

Its detractors argued that the foundation of an authentic GT racing class (in Australia at least) was that all cars must be based on the same technical specification as road-going models. The largest engine available in a new Monaro at the time was a Gen III 5.7 litre V8, so the decision to install a 7.0 litre version - when no such variant was available in the showroom - was not seen to be in the spirit of the rules.

In its defence, Holden claimed that it had built a car which complied with regulations laid down by PROCAR, organisers of the Australian Nations Cup Championship (ANCC). Under PROCAR boss Ross Palmer, the Nations Cup formula established in 2000 was admirably designed to showcase each nation's best GT cars. On reflection, given the global popularity of today's very similar GT3, it would be fair to say that Palmer was a visionary and ahead of his time.

He also knew that a strong Australian representation would be crucial to the success of Nations Cup and wanted Holden to join the battle. The General was certainly keen to promote the sporting prowess of its new Commodore-based coupe, but V8 Supercar racing was not an option as only four-door sedans were eligible.

The burgeoning Nations Cup, however, was a no-brainer and Palmer bent over backwards to get the roaring lion involved. However, he perhaps bent too far in allowing the 8.0 litre V10 Dodge Viper to be used as a benchmark when approving use of a 7.0 litre (427cid) engine in the Monaro. No other Nations Cup contender was granted the same special treatment, hence the controversy.

A month before the race, at the 2002 Sydney Motor Show, Holden/HSV revealed a road-registerable competition version of a 7.0 litre Monaro called the HRT 427. With only 50 to be built, with a price tag of more than $200,000 each, it was aimed at traditional Porsche territory where wealthy club racers compete in bitumen road rallies and popular one-make racing series like the Porsche Cup.

Holden claimed that the Nations Cup 427 and HRT 427 were separate projects. Even so, the obvious fringe benefit of the proposed road-legal supercar was to quell criticism that the Nations Cup car had no road-based derivative. On reflection, it would have been better if PROCAR insisted the batch of HRT 427s be built before granting approval of the Nations Cup racer, but the timing of the two projects made that impossible.

As it turned out the HRT 427 proposal was shelved within a year, due to cost blow-outs caused mainly by ADR compliance for road use which made the ambitious project unviable. The demise of HRT 427 was in fact timely for Holden, as the whole PROCAR show was about to self-destruct anyway.

By 2004 a disillusioned Ross Palmer had given up on his largely self-funded dream and with his departure from the sport went the short-lived ANCC and Bathurst 24 Hour race.

And of course the Nations Cup Monaro 427C, which did not comply with Australia's new era of GT racing; an orphan destined to pass into motor sport history as one of the most awesome and curious Holden race cars ever conceived.

Le Mans on the Mountain

The 7.0 litre Monaro made its debut at the inaugural Bathurst 24-Hour race in November 2002. It was the first 24 hour event to be held at Mount Panorama.

Holden's ambitious plan for the Monaro to tackle a twice-around-the-clock endurance race straight out of the box could be traced back to November 2001, when top secret construction commenced at the V8 Supercar workshops of Garry Rogers Motorsport.

Original planning for the car, under Holden Motor Sport chief John Stevenson, was to tackle the 2003 ANCC series, but the project suddenly faced a much shorter deadline after the Bathurst 24 Hour race was announced early in 2002. Holden wanted in, so suddenly a car that was being built for a series of short sprint races the following year had to be reconfigured within months for racing around Mount Panorama non-stop for 24 hours.

Although most of the chassis build, with its massively rigid roll cage and 120-litre fuel cell, followed well established V8 Supercar practice, there was some major pioneering work required in the areas of engine and suspension.

The Monaro's locally-built 427cid V8 was based on the LS1 Gen III-derived all-aluminium six-bolt mains cylinder block and heads used in Chevrolet's highly successful Corvette C5-R Le Mans racer. This allowed Holden to access a proven development off-the-shelf from GM's global performance parts store. Forged crank, rods and pistons were sourced from respected US after-market suppliers, but the cross-ram butterfly throttle inlet manifold was designed by GRM engine builder Mike Excel and locally made.

Holden expected an electronic rev limit of 6700rpm to be imposed, in comparison to the 7500rpm limit used in the 5.0 litre V8 Supercars. Although no official dyno figures were released, Stevenson suggested at those lower revs the 7.0 litre engine would produce at least 550bhp. That was about 50bhp less than a 5.0 litre V8 Supercar but with considerably more torque due to its longer crankshaft stroke and 2.0 litre increase in cubic capacity.

By the time the Monaro arrived at Mount Panorama, PROCAR had set a limit of 5700rpm – a full 1000rpm lower than expected. Although that may have reduced the engine's power output, it still had enough bulldozer-grade torque to move mountains. The big rpm drop also improved fuel economy and particularly durability margins.

A six-speed Holinger gearbox bucked V8 Supercar's H-pattern tradition by using a sequential shifter like the Dodge Viper, to avoid the risk of engine-damaging missed shifts. And to keep the revs down, the Monaro ran a very tall 2.85:1 final drive ratio.

Like the gearbox, brakes were also proven V8 Supercar hardware with huge AP Racing 380mm ventilated front rotors clamped by six-pot calipers and smaller rotors and four-pot calipers in the rear.

The Monaro was approved to run the same 18 x 13-inch rear wheels and tyres as used by Lamborghini Diablo and Dodge Viper rivals. This required fabrication of extra-large internal wheel tubs for adequate clearance to avoid the need for external wheel arch extensions. Front wheel/tyre size was a more modest 18 x 11-inches. The Commodore V8 Supercar-style aerodynamic kit included a front spoiler, twin-post rear wing, rear bumper diffusor and side skirts.

The Nations Cup rules required retention of the road car's suspension design, so front McPherson struts using a lot of existing Commodore V8 Supercar hardware were adapted. However, Holden was forced to cast aside the Commodore's equally well-proven V8 Supercar live rear axle set-up and venture into new territory with its own version of the Monaro's independent rear suspension (IRS).

"We looked at various concepts including beefing-up the production IRS unit, but after two months of research we decided to design a new competition IRS from scratch," John Stevenson told AMC magazine at the time.

"That decision also dictated that the Monaro's roll cage design would be quite different to a V8 Supercar, because it would need to tie-in with the different attachment points for the IRS, as well as the restrictions placed on front strut tower reinforcements by PROCAR rules. It was quite a complicated process, using Ron Harrop's CAD system modelling to work out the best solution."

The obvious question - was the Monaro 427C faster than a Commodore V8 Supercar? In theory you would have thought so, given the same 1350kg minimum weight target plus more rubber on the road, arguably a more slippery shape and an engine 2.0 litres' larger in capacity!

In practice, however, Holden never let this animal off its leash. It always raced with punitive engine restrictions which ensured it was massively under-stressed and provided only a glimpse of what must have been formidable potential. Even so, it still had a deep booming exhaust note reminiscent of the loping big block 7.0 litre Ford GT40 Mark IIs which blitzed Le Mans in the 1960s.

2002 Bathurst 24 Hour

The Nations Cup Monaro had only completed about 500km of testing and parity evaluation at Winton Raceway prior to its arrival at Mount Panorama for the first running of the Bathurst 24 Hour race. The youthful four-man driving squad comprised V8 Supercar regulars Garth Tander, Steven Richards, Cameron McConville and Nathan Pretty.

Although Holden had started the project with a build target of 1350kg, by the time it arrived at Bathurst PROCAR had raised its minimum weight by 50kg to 1400kg along with the low 5700rpm engine limit.

The first Bathurst 24 Hour attracted a healthy 36-car entry representing a variety of categories under the PROCAR umbrella including Nations Cup, GT Performance and GT Production. The field was broken up into five classes or 'groups' with the winner expected to come from Group One which included the fastest Nations Cup contenders and cars complying with international GT rules.

Despite some teething troubles during practice the Monaro qualified on the front row, alongside the Prancing Horse Racing Ferrari 360 in which Brad Jones claimed pole position with a time of 2 min 15.07 secs. Garth Tander went quicker later, though, when setting the fastest race lap at 2 min 14.32 secs. Considering the V8 Supercars of the era were capable of sub-2 min 10 sec laps many expected the 7.0 litre Monaro to be much faster, but clearly it was only going as fast as it needed to.

In a dream debut the thundering yellow beast crossed the finish line first, after covering 532 laps (compared to only 161 in the annual 1000km race) and a total distance of 3305km in 24 hours – or the equivalent of more than three Bathurst 1000s non-stop! Its winning margin was a staggering 22 laps.

Such a big win, though, was more challenging than it looked and not without dramas. For starters, some of the fabrication points on the carrier for the diff centre in the new IRS weren't strong enough. Some minor upgrades were made after the Winton test, only for the assembly to break in the last practice session at Bathurst on Friday which cost a shot at pole position. GRM mechanics re-engineered it that night and cured the problem.

Then after leading the race for four hours, the scavenge pumps in the fuel tank failed after running the tank nearly dry after about 38 laps between stops. The team thought the failure may have been caused by the pumps overheating, even though GRM had never suffered that problem using the same pumps in their V8 Supercars. As a precautionary measure they set a maximum of 30-31 laps between fuel stops and suffered no further problems, but time lost in the pits doing repairs dropped the Monaro 13 laps down the leader board.

That was the start of a determined but steady fightback, partly hindered by the 7.0 litre engine throwing three alternator belts which required more lateral thinking. The car had only been tested prior to the race at the relatively low-speed Winton circuit. At Bathurst, though, they discovered that the much higher rpm at top speed in top gear down Conrod Straight (approaching 300km/h) was causing enough flex in the belts to make them fly off. The drivers were told to slightly reduce their speeds on Conrod which fixed the problem.

The Monaro also took a big hit in the driver's side during the night when Nathan Pretty collided with a lapped car and spun off, fortunately without hitting anything. However, the sequential gearbox was stuck in gear and the car could not be restarted. On the two-way radio the pit crew told Pretty to get out and rock the car backwards and forwards to free it up and it worked. He was able to drive it back to pits for some hasty body repairs before continuing.

Ultimately the battle for the lead came down to the Monaro and the Brabham/Jurez/Grice/Palmer Porsche 911 RS GT3. Holden could not believe its luck when the rapid Porsche had to make a lengthy stop to replace a broken driveshaft in the 19th hour, which put the Monaro back in front and a lead it would not relinquish.

2003 Bathurst 24 Hour

If Holden was suffering from perceptions of 'overkill' by using a 7.0 litre engine, such criticism strengthened in 2003 when GRM returned with two Monaros to defend its Bathurst 24 Hour title. Against almost non-existent competition, they finished a resounding 1-2 with a winning margin of 11 laps.

The original yellow car, which had won the 2002 race and been driven by Nathan Pretty to third place in the 2003 ANCC, was reunited with its previous year's driving squad comprising Tander, Richards, McConville and Pretty.

GRM's construction of a second car, turned out in Holden Motor Sport's corporate red, had been personally funded by PROCAR boss Ross Palmer for Peter Brock to drive. The plan was for the nine-time Bathurst 500/1000 winner to campaign the car in the 2003 ANCC before joining a four-driver squad for the 24 Hour comprising Holden V8 Supercar regulars Greg Murphy, Jason Bright and Todd Kelly.

The two-car Monaro team under GRM not only had strength in numbers but was also better prepared, armed with valuable experience from the previous year's race and some heavier duty components. Revs were capped at the same 5700rpm limit and the 7.0 litre engines were also fitted with air intake restrictors imposed by PROCAR. Not that it made any difference.

The entry had grown from 36 to 45 cars. Increased competition was expected to come from the UK's Rollcentre Racing with its potent Chev V8-powered Mosler MT900R and a Porsche 996 GT3 entered by Germany's Jurgen Alzen Motorsport.

The Monaros claimed the front row. Garth Tander took pole position (2 min 13.28 secs) with a time almost two seconds faster than the previous year's, yet his fastest race lap was virtually identical to the one he set in 2002. It was clear that these cars were only being driven as fast as necessary, with plenty in reserve had a genuine rival emerged.

As expected, the Monaros had the race by the throat from the start and enjoyed a near faultless run. The only problem emerged late in the event when it was claimed that the diff oil temperature in the leading yellow car had started to climb due to a faulty oil pump. A quick stop to hook-up a replacement pump allowed the red '05' car into a lead it held to the end, despite the yellow car closing right up in the final laps.

Critics claimed that the oil pump problem was stage-managed by PROCAR and Holden to ensure Brock's red car won and delivered his long-awaited 10th Bathurst win. If so, it was all for nothing because only a win in the traditional 1000km race counted as far as Brock fans and historians were concerned.

On reflection it was a shame the Nations Cup Monaros, as awesome as they were, ended up as racing orphans following the death of PROCAR in 2004. Even though a UK team showed interest in running the cars badged as Vauxhall Monaros in British GT racing, nothing came of it. So, dreams of these unique Aussie coupes thundering around Le Mans and Daytona at 200mph-plus, sadly have remained just that.