The Year Australia was sold a Pup and not a Pony

The Mustang was the first US pony car prepared by an Australian arm of the original manufacturer for local Right Hand Drive requirements before it was officially sold across the entire mainstream dealer network.

A small batch of Chevrolet Camaros was later stocked by selected Holden dealers and Australian Motor Industries (AMI) assembled the Rambler Javelin. Yet it was the Mustang that had the biggest impact after the first Mustang arrived in Australia two days before the model's global release.

The arrival of the Mustang in Australia occurred in two stages under two entirely different rationales. The Mustang's lead time coincided with an Australian shift in national focus from the British Commonwealth to a more global perspective. Australian manufacturers could source current US models directly from Detroit head offices for the first time since the end of World War II.

All local Ford operations involving North American models prior to this shift had to occur via Canada. During the early 1960s, Ford of Canada was also made a satellite of Detroit. Senior Australian engineers and management on assignment in Canada recall being flown over the border as soon as this was announced. For the first time, Australians were working alongside the movers and shakers at head office, many of whom were working on the Mustang.

After the locally-assembled "compact" Fairlane marked a return to current US models in 1962 followed by the Galaxie in 1964, the 1966 XR Falcon marked the first post-1945 Australian Ford that emerged from this new direct liaison with Detroit. Both developments ensured that the Mustang would become part of the Australian streetscape.

The Mustang Six-Cylinder Strategy

Lee Iacocca's passion for the Mustang was so infectious during the 1962-63 period that it prompted an informal gathering in the Dearborn Inn of senior Australians recently transferred from Canada. The consensus was that it should come to Australia. As dealers were already up to speed on the local Falcon sixes, investment in parts and service training would be minimal.

The first decision to import 200 Mustangs was made in the context of the pre-1966 Australian six-cylinder Falcons. The local rejection of the 1964-65 restyle of the US Falcon for Australia was a gritty but inspired plan at a time when Australians were demanding more substance from the Falcon, not more style. Importing the Mustang along with the necessary panels to create the XM and XP Falcon Hardtops were part of a strategy to add extra glamour and credibility to the ageing 1960 Falcon starting point. This bought time for the engineers to make a local Falcon unbreakable.

As early as 1963, the late Les Powell, Ford Australia's Public Affairs staffer who became Ford's long-suffering de facto head of motorsport, prepared a detailed document on establishing a credible Ford motorsport presence to give the Cortina and Falcon an edge over the competition. These documents confirm that Powell had also identified the coming Mustang as Ford's best potential Touring Car track weapon. Although Bill Bourke would later help Melbourne driver Norm Beechey jump the US queue to get into a Mustang following a chance meeting in a restaurant (see Mark Oastler's article on racing Mustangs in Australia), the rationale was already established in the Ford Australia psyche.

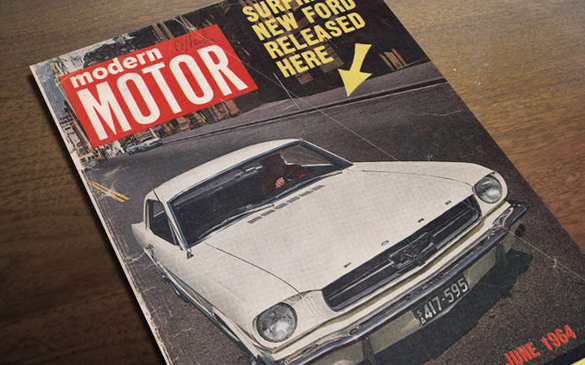

For evidence of this earlier thinking, look no further than Modern Motor, June 1964, which featured a Mustang Hardtop on the cover that had arrived in Sydney two days before the Mustang's global release in April 1964. Tester Ian Fraser was amongst the first outside Ford to drive a Mustang on Australian soil when he was given a brief drive of the South Australian registered LHD Mustang. It was a 170ci six with three-speed floor shift manual hence Fraser's suggestion that "Mustang means to Falcon what the Karmann-Ghia does to Beetle and Caravelle to the Renault R8".

As both Europeans had small but highly visible local followings, the evaluation car's basic Falcon drivetrain positioned the Mustang as a special order six-cylinder Falcon image booster, in line with Ford Australia's plans. It also reflected what would have been the most popular local specification in 1964, 18 months before the Chrysler AP6 Valiant V8 challenged Australia's entrenched six-cylinder loyalties. It was also perfectly timed to challenge the MGB, a model just launched after it went into local production in 1963. The MGB's extra practicality made it an instant success, which the Mustang could better.

Fraser dutifully concluded that the Mustang presented the stock Falcon's mechanicals in an unexpectedly positive light, even giving "a new lease of life to the otherwise dowdy three-speed Falcon box." After Fraser correctly predicted that the Mustang would be a runaway global success, his local conclusions were predicated on the projected $4000 price, close enough to what the few basic six-cylinder models cost when they did arrive in 1965.

The Mustang V8 Strategy

In mid-1963, a massive internal change at Ford Australia was underway that would later add another two cylinders to this strategy. Wallace Booth, a former US retail specialist who had come through the ranks of Ford in Canada as a finance man, was posted to Australia as Ford's first highly visible managing director. He cannily identified Bill Bourke, a rising US Ford marketing whizz, to help him overhaul Ford Australia.

It was Bourke who made it a priority to demonstrate to the Australian public that the engineering job on the Falcon was complete by initiating the horror 70,000 miles at 70 mph endurance run (113,000km@113km/h) at the company's You Yangs proving ground in 1965.

Bourke's challenge was to then convince Australians that the cumulative gains evident in the last of these first generation Falcons had all been successfully transferred to the 1966 US model. Australians had learnt the hard way that a new US model usually brought a new round of problems. The 1966 US Falcon added an even more serious scenario. As a budget compact in the US, its short-tail, long-nose styling was on the money. As a long distance full-sized Aussie family car, it suggested an undersized boot, poor fuel tank range and a return to US frivolity that burned so many local Falcon buyers in 1960. By 1966, the Falcon's local competition was unusually strong on luggage space and fuel range.

As local engineers re-designed the boot and fuel tank to maximize space and range, Bourke was on a mission to convince Australians that the 1966 Falcon styling was so sexy that nothing else mattered. By offering Australia's first V8 option across a family car range, Bourke ensured that the 1966 Falcon could never be dismissed as a show pony. Tough enough to be Australia's most powerful V8 family car equals tough enough to work for any Australian as a six, was the subliminal message, later reinforced by the first local Falcon GT.

The role of a local Mustang suddenly went from a sideline image booster to a critical pillar to establish the next local Falcon's looks and performance. Bourke decreed that every Australian needed to know what a Mustang looked like. The often-quoted 435 local Mustang sales figure is based on one for every Ford dealer in Australia although the actual figure may have been closer to the original 200. The local Mustang's role had expanded from validating local sixes to showcasing the 289/4.7-litre V8 and C4 automatic central to the coming 1966 XR Falcon's credibility.

Bourke would then tie it all together by launching the 1966 Falcon under the potent Mustang Bred campaign. As Bourke's strategy also harnessed the combined successes of local Mustang track cars, Ford's promise of a Falcon family car that looked and performed like a Mustang soon became a source of real excitement. Yet the strategy almost came unravelled at the most critical point.

What the?

The alleged symmetry of the Mustang dash and firewall had led Australians as far back as 1963 to believe that a RHD conversion by Ford's expert team at the Homebush plant near Sydney would be a doddle. After Bourke was told the same story by his American colleagues, the Homebush plant was left to meet his tight deadlines without engineering input from the Melbourne head office. The results were not pretty.

Bill Tafe, Homebush's manufacturing engineering manager, not only had to make the conversion happen but Bourke directed that he personally sign off on the quality of each car. Tafe wisely insisted on a batch of Mustang dashes to be air-freighted to Australia ahead of the cars. The Mustang dash was anything but symmetrical. As today's Mustang conversion experts could imagine, the dash was only the start of the Homebush nightmare:

Tafe immediately enlisted a trusted old school sheet metal expert close to the plant whom he knew only as Mr Morrison to re-manufacture the original dash. Despite the extensive work required, the dash was one of the few aspects that went to plan.

The first Mustang's arrival confirmed that the firewall needed to be removed and either re-manufactured or replaced for a proper mirror conversion. Bourke's deadlines didn't allow for this.

Local Mustangs started arriving in early 1965, all Hardtops with front disc brakes and a mixture of entry level 289/4.7 V8 with C4 automatic transmission and sixes. Because local deliveries straddled US model years, Homebush Mustangs came in 1965 and 1966 US specifications.

Each car had the Shelby-type one piece stirrup-shaped strut tower brace, not the more common two-piece braces.

There was no room for the integrated LHD large bore master cylinder /vacuum booster on the RHS. It was replaced with a large bore unassisted master cylinder and a separate local PBR vacuum booster mounted on the LHS.

Washers were welded under the shocker mounts as for Shelby cars to counter severe local road conditions.

The entire Mustang heater system except for the slide controls was scrapped as it couldn't be swapped over. A local Falcon unit was fitted and a new firewall bulge provided space for the plumbing.

The cardboard glovebox insert was reworked to clear the wiper motor.

The scrapped heater unit left a large bulge in the RHS firewall which moved the steering forward enough to change the steering geometry. The stock Mustang column had a compact Fairlane inner column with a rag joint so it could mate up with the Fairlane steering box.

The RHS lower suspension tower had to be bashed in to allow room for a steering box now forced forward and bolted to the front subframe member. The box section was reinforced with an internal tube.

Tafe used compact Fairlane drag links and idler arms with crude cone-shaped sleeves to mate up with the original tie-rod ends. This left Homebush Mustangs with disturbing bumpsteer at speed. A March 1966 Modern Motor report summed up the result: "It made me feel 10 years younger when I first drove it; it took 10 years off my life the first time I tried to corner it hard."

A flared opening was cut into the firewall for the handbrake. Wiper positions remained as for LHD.

A "Ford Motor Company of Australia" Vehicle Identification Plate was attached near the top of RHS front guard next to the suspension tower. The Australian number featured the last five digits of the car's US identification, the time lag confirming local memories of unconverted Mustangs packed into the Homebush yards for months.

The LHS suspension tower tag carried a date and X for export. An LHS door plate carried a DSO 90-99 code for a Domestic Special Order Export build. A DSO 95 code seemed to be the most common.

So pent up was local demand for a Mustang in a market that had been starved of sporty US models, they sold as soon as Homebush could spare the manpower to convert them. This was despite retail stickers that placed them above the desirable Aussie-built Galaxie.

As Homebush was also under pressure to increase local content in the RHD Galaxies and F-series trucks, these Mustangs were still being cleared at the end of 1966, some say as late as 1967. Yet they achieved their objective in spades. Because most subsequent owners assumed these cars were backyard conversions that demanded rectification, few survive in their original specification.

Thanks to Colin Falso, early Australian Mustang owner and expert, for confirmation of conversion details and several images.