Mazda R100: The first Mazda rotary at Bathurst

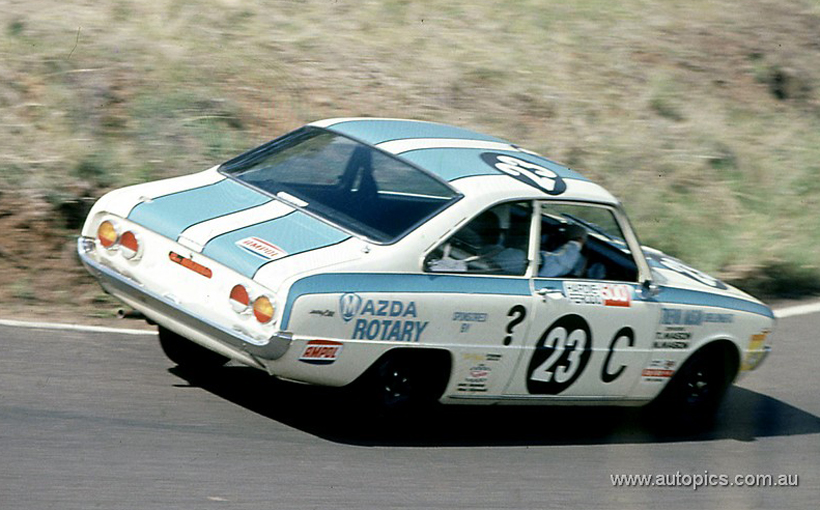

The R100 driven by Trevor and Neil Mason charges through The Dipper in the 1969 Hardie-Ferodo 500. Note the round tail lights, one of few distinguishing features between an R100 and its piston-engined 1200 Coupe sibling.

The 1969 Hardie-Ferodo 500 not only heralded the Bathurst debut of burgeoning Japanese car manufacturer Mazda with its R100 coupe, but it was also the first time spectators heard the bizarre exhaust note of a rotary-powered production car at Mount Panorama.

The Wankel rotary-powered cars, strangled by standard road-legal exhaust systems required at the time, emitted a muffled noise similar to that made when tearing a large sheet of paper. Spectators could have been excused for thinking it would be the first and last time they’d see such curious engine technology at Bathurst, but it was just the beginning.

Over the next 15 years, increasingly refined, faster – and noisier - examples of Mazda’s rotary-powered ‘RX’ models would compete with enviable class success, including the RX-2, RX-3 and RX-7. And in the 1990s, Mazda returned to Bathurst with the latest twin-turbo RX-7 to dominate the annual 12 Hour production car race.

The R100 driven by Garry Cooke and Geoff Spence was the slowest of the three Mazdas in qualifying at Bathurst in 1969 but finished the race as the highest placed thanks to solid preparation, good driving and pit stops.

Mazda was a late starter in terms of Japanese car makers on the Mountain. However, like its domestic rivals Isuzu, Toyota, Datsun and Honda, it knew the annual 500-mile (800 km) production car race was essential in any local marketing plans.

Proving a Japanese car’s durability when subjected to the extreme demands of competition was of particular importance to Mazda, as it had decided to back the then radical concept of Wankel rotary engine power.

Parent company Toyo Kogyo had secured the rights from Germany’s NSU-Wankel in 1961 to produce its rotary engine under licence. And had spent the best part of a decade in research and development, to solve not only the rotary’s infamous durability issues (think NSU’s disastrous Ro80 sedan) but also greatly increase its performance in motor sport by mastering the unique science of peripheral porting.

The R100 shared by Formula Vee top gun Bernie Haenhle and motoring journalist Peter Wherrett showed competitive pace in qualifying to be up amongst the fastest contenders in Class C. Unfortunately this car was badly damaged in a roll-over during the race, which created its own compelling piece of Bathurst history (see story).

The smooth, free-revving and extremely compact Wankel engine offered a far superior power-to-weight ratio to conventional piston engines and the unmatched simplicity of a combustion cycle which required only one moving part. On the minus side the rotary didn’t mind a drink and its exhaust emissions were high, but in the 1960s such concerns were barely a blip on the radar.

Its debut in the striking Mazda 110S sports car in 1967 grabbed the world’s attention but the next critical step for Toyo Kogyo in its bid for global acceptance of the rotary was to install one in a normal passenger car, which could be mass-produced in series production.

The donor model chosen was Mazda’s humble 1200 coupe, which was renamed the R100 with the ‘R’ denoting its rotary engine and the ‘100’ covering its impressive horsepower output. On reflection, the R100 was in effect a production prototype for the high performance rotary powered ‘RX’ models which would soon follow.

The R100 was the first of several rotary-powered ‘RX’ Mazdas which achieved great success in Australian touring car racing. In the early 1980s the RX-7 became a giant killer in an audacious attack led by Allan Moffat in his magnificent factory-backed RX-7s. At their peak in 1984 these factory racers were powered by fuel-injected peripheral port 13B engines.

Released in June 1969, there was little to visually differentiate the R100 from its 1169cc piston-engined sibling, sharing MacPherson strut front and leaf-sprung live axle rear suspension and front disc/rear drum brakes, but standing an inch taller on larger 14-inch wheels.

Under the bonnet was Mazda’s free-revving 10A motor consisting of two 491cc rotors with a combined cubic capacity of only 982cc. And although the 10A looked like a small beer keg, its prodigious power output of 100 bhp (75kW) seemed implausible against the mere 73 bhp of its 1200 cousin.

Although maximum power was reached at 7000 rpm the R100’s tacho displayed a 6500 rpm redline backed by a mechanical cut-out at 7000 rpm, as Mazda engineers were rightly concerned about protecting their hard-earned durability margins in such a free-revving engine. The R100 also boasted torque of 100 ft/lbs (136Nm) at 4000 rpm compared to the 1200’s 72 ft/lbs (98 Nm).

With only 805 kg to shift, the swoopy fastback could clock the standing quarter in less than 18 secs with a mighty top speed of 110 mph (175 km/h). However the R100 wasn’t as competent through the corners. It was very narrow and tall relative to its length, resulting in lots of body roll and some fearful roll oversteer at high speeds caused by toe-out on the outside rear wheels due to deflection in the leaf springs.

The mighty performance of the new Mazda R100s at the 1969 Spa 24 Hour race in Belgium showcased the speed and reliability of the Wankel rotary engine for all the world to see. The diminutive Japanese cars were beaten only by factory-backed Porsche 911s. An R100 also finished top five in 1970. Images: www.automotivpress.fr

Proving the product

Three factory-backed R100s were entered in the 1969 Spa 24-Hour, a classic race for production-based cars held each year at Belgium’s daunting 14 km Spa-Francorchamps circuit. The huge multi-class grid for 1969 comprised its usual dazzling mix of different makes and models, with the outright fight tipped to be between thoroughbreds from Porsche and BMW.

After the BMW challenge faded the factory-backed Porsche 911s finished a resounding 1-2-3-4, but what most observers had not expected to see after 24 hours were two of the Mazda R100s nipping at their heels in fifth and sixth. The third Mazda had been eliminated in an accident earlier in the race.

In an astonishing first-up display of twice-around-the-clock durability, the little rotary-powered rockets just kept going and going, displaying competitive speed and faultless reliability while many of their piston-engined rivals fell around them.

The highest placed of the three works Mazda R100s at Spa in 1969 was the No.29 entry shared by Belgium’s Yves Deprez and Japan’s Yoshimi Katayama. This car finished a fighting fifth outright behind the Porsche quartet, after completing more than 4,000 km in 24 hours. That was the equivalent distance of more than five Bathurst 500s non-stop! Image: www.automotivpress.fr

The 10A engines were reportedly equipped with Mazda’s race-only peripheral porting, which was permitted under the event’s Group 5 rules. With such improved breathing they were capable of power outputs approaching 200 bhp, but in 24-hour trim the revs were dropped and power capped to ensure the engines could complete such a huge distance without a hitch.

Only a few months later, the R100 was thrust into a different battle half a world away at Bathurst in the annual Hardie-Ferodo 500 on Mount Panorama. Although it was ‘only’ about a fifth of the distance covered in Belgium, the Bathurst rules were framed around stock standard production cars without any of Europe’s Group 5 freedoms.

Local Mazda distributors and dealers were keen to capitalise on the R100’s success at Spa by subjecting it to a similar durability test in Australia’s toughest race. Back in those days, competing cars were grouped according to their showroom prices. With a local retail of $2790, the R100 was eligible for Class C which catered for cars between $2251- $3100.

The fast but ill-fated Haenhle/Wherrett R100 powers through Forrest’s Elbow at Bathurst in 1969. This angle shows how high these cars rode in their skinny 14-inch steel wheels and how tall and narrow the body was relative to its overall length. They looked like they could easily tip over at high speeds and some of them did – including this one!

Once again the battlelines were drawn between British Leyland’s all-conquering Mini Cooper S and any new class contender brave enough to try to topple it. Since its debut in 1965, the mercurial ‘flying brick’ had seen off all challengers to claim four straight Class C victories including an outright win in 1966.

In 1969 the Cooper S faced competition from not only the very quick Fiat 125 which showed impressive pace the previous year but several fresh-faced challengers including Chrysler’s new slant six-powered VF Valiant Pacer, Renault’s 16TS, Ford’s Capri 1600 GT – and three of the new Mazda R100s.

During official practice, the scintillating top speed of the new rotary-powered Japanese contender was put to good use on the long straights. The R100s were producing competitive lap times but also anxious moments for their drivers as they explored the limits of the Mazda’s chassis dynamics.

Garry Cooke uses his helmet visor to shade his eyes from strong sun as he powers his R100 through the notoriously steep and off-camber Castrol XL Bend at Bathurst in 1969. It was at this corner that the Haenhle/Wherrett Mazda would come to grief early in the race.

Journalist Peter Wherrett, who would famously host the ABC’s ‘Torque’ motoring show in the 1970s, shared an R100 with Formula Vee ace Bernie Haenhle backed by Sydney’s Denlo Motors. In his autobiography ‘The Quest for the Perfect Car’ Wherrett vividly recalled the R100’s wayward handling:

“I knew a little about the R100. It was the compact Mazda two-door ‘sports’ sedan fitted with a rotary engine, a power unit of considerable performance. But I also knew the handling and brakes were limited and I had to wonder how it would perform on the mountain,” Wherrett wrote.

“It didn’t take long to find out. Bernie took the first practice session and when he came in he told me, in his strong German accent, that it was ‘a bit hairy’. He was putting it mildly. The car had been constructed on a narrow track and the track-to-wheelbase ratio was all wrong; that is to say, it was either too long or too narrow, one or the other. It was a big oversteerer, with the rear end wanting to slide out at every opportunity, so it was hard work keeping it pointed in the right direction.

“Nevertheless, with the power available and the long straights, we were able to record some respectable lap times that placed us near the top of our class.”

“Watch your mirrors” was the best advice for drivers of small cars in the Hardie-Ferodo 500 when it hosted a huge variety of competing cars small, medium and large. This shot shows the disparity in size between a Falcon GT-HO, Mazda R100 and Datsun 1600. Also note the absence of safety fencing at Bathurst in those days; just plenty of good solid trees to stop you.

The Haenhle/Wherrett Mazda qualified fourth fastest behind the new Pacer and a pair of S-type Coopers. The second R100 shared by Trevor and Neil Mason was only 0.1 sec shy of Haenhle/Wherrett with the third Mazda crewed by Garry Cooke and Geoff Spence further back behind another Cooper S and a Fiat 125.

The times between the hot contenders were very close in what promised to be a great inter-brand battle. However this was disrupted somewhat by the enormous pile-up at Skyline on the first lap of the race, after Sydney newsagent Bill Brown rolled his Falcon GT-HO near the front of the pack and triggered a multi-car wreck that threatened to stop the race. A few laps later an R100 would add to the race wreckage, in what has become one of the Mountain’s most memorable moments.

The herculean effort by Bernie Haenhle in using nothing but fence posts, tree branches and bare hands to get his rolled R100 back on its wheels all by himself and then drive it back to the pits during the 1969 Bathurst race is Bathurst legend. Look how close Bernie was standing to the edge of the track, where cars would whiz past close behind him for lap after lap. It’s a pity his efforts were all for zip in the end.

“On race day Bernie took the first session and I joined the pit crew to watch his progress,” Wherrett continued. “Bernie was an exuberant, talented driver and near unbeatable in Formula Vee, but touring cars were a whole new experience for him. It is common to run race laps a few seconds off your best practice time for conservation purposes. A race of 500 miles, which it was then, is a long way but Bernie was close to practice lap times lap after lap.

“About twenty laps into the race (31 laps: MO) he didn’t come past the pits when he should have and we began to wonder what had happened. The television coverage soon told us. He had lost control climbing the mountain, dropped off the side of the track and rolled the car. So that was that.

“Except that it wasn’t. After sitting and considering the situation for a while, Bernie decided he could get the car back on its feet. He found a long, strong limb of a tree and, using it as a lever, produced one of the great feats of Mount Panorama. Working away for well over an hour he managed to get the Mazda back on its wheels, started the engine, drove up the embankment and onto the track and eventually brought the car back to the pits.

The Garry Cooke/Geoff Spence R100 has its driver’s mirror filled with a big booming Monaro GTS 350 at Bathurst in 1969. The little Mazda rotaries proved to be very reliable, even if their handling and engine thirst left a bit to be desired.

“Although the car was driveable the officials would not let us re-join the race because there was no windscreen. We figured we could knock out the rear window and drive with goggles – with full flow-through ventilation – but the officials would not relent. So all Bernie’s work was to no avail.

“That is, but for one significant point. As a mid-field competitor our chances of producing any television exposure for Denlo Motors and other sponsors had been extremely remote. Bernie’s effort with the tree was a real-life drama which resulted in many minutes of television coverage. Not surprisingly, Dennis Whitehead (dealer principal) was delighted. But I wasn’t; I didn’t even get a drive.”

The fastest of the two remaining R100s finished fifth in Class C behind the winning Cooper S, two Fiat 125s and the lone Valiant Pacer. The second R100 came home seventh. The two Mazdas finished on the same lap, which was a full two laps behind the winning Mini with its superior handling and fuel economy.

The Mazda R100 driven by Trevor and Neil Mason greets the chequered flag as it finishes seventh in Class C in the 1969 Hardie-Ferodo 500. It was the first shot fired in anger at Bathurst by the innovative Japanese manufacturer which would grow to become a prominent and respected force in Australian motor sport and worldwide.

The R100s had been clearly outclassed by some of their price-based market rivals. However, what was of utmost importance to Mazda was that two stock standard examples of its new mass-produced rotary engine survived 500 miles flat-out on one of the world’s most challenging circuits without a hiccup.

It all happened in full public view of course. And in those days, all the money in the world could not buy you such instant credibility. At the dawn of a new decade, a bright future beckoned for Mazda in Australian touring car racing - and it all started with the R100.