Holden Torana GTR XU-1: the General’s David to tackle Goliath

The Holden Torana GTR XU-1 is one of many great Australian classic cars that would never have come into being if it had not been for a 500-mile race at a rural race circuit west of Sydney.

In 1987, many years before these cars were worth serious money, I produced the first ever magazine devoted solely to Toranas. The late Geoff Paradise was the publisher, the title was The History of Torana: from Viva to Victory, and we persuaded one Peter Brock to write the introduction.

Here’s what Brocky had to say:

TORANA – the name always sounded good to me. Sort of like ‘Corvette’ to the yanks I suppose. And let’s face it, the first version with any potential go was Aussie ingenuity at its best. Cranking what was then a big six into your basic small economy job was a definite chance.

My introduction to Torana was late in 1969. Harry Firth had the mission of making a winner out of the soon-to-be-released GTR.

The Monaro GTS 350 had just won Bathurst and ‘H’ had dropped a bit of a bombshell to the guys in the Dealer Team saying next year we would be running a six!

In retrospect I guess Firth figured that since my little Holden 179-powered A30 developed about 247 bhp that this young bloke named Brock may be of some use after all. The Firthery had only just severed links with Ford and undoubtedly had some future product information which he put to good use.

Chief mechanic Ian Tate set to work on a GTR Torana (rego KLD-158) by despatching the 161 and installing a 186 which was brought to a mild state of tune. It sported a speed shop inlet manifold, a mild camshaft which had the same grind as the one in my EJ tow van. In essence, the prototype XU-1 stated life with a healthy 186 with perhaps a few more horses than the first XU-1.

I drove this car everywhere. Around the streets of Melbourne, the backblocks of Victoria and even down to the corner shop. My report sheet indicated that a number of mods be carried out for the production car. I don’t mind telling you it was a great thrill to be involved in the development of a car like this – after all, I had only been racing for 23 months.

This was not quite the same as the story that the GM-H publicity machine concocted for its press release for the LC XU-1 in August 1970:

GMH today announced the Torana GTR XU-1, an additional model to the LC Torana range introduced in October last year.

Fitted with a three carburettor 186 cu. in. engine, the XU-1 is in fact a higher performance version of the GTR sports sedan. The XU-1 has been developed to meet strong demand for such a vehicle from motoring enthusiasts.

An initial batch of 700 cars will be built to meet immediate demand, to be followed by further production if subsequent demand re-warrants. The increased engine capacity of the XU-1 has resulted in numerous engineering refinements designed to improve overall handling and performance.

Front and rear suspension modifications, larger disc brakes with an increased capacity booster, front and rear spoilers and a greater radiator cooling capacity are the major items.

The XU-1 is fitted with a 17 gallon fuel tank to increase the car’s touring range. Principal external distinguishing features are the rear spoiler, GTR XU-1 decals, and exclusive bold colour range.

Apart from some torturing of the English language – especially ‘re-warrants’ – the XU-1 was clearly not developed to meet a demand already existing in the market. This was the General’s too-cute way of glossing over the obvious: the GTR XU-1 was conceived precisely to win at Mount Panorama. But in 1970, only industry insiders would have had any inkling that the entire development program for the car took place at Harry Firth’s headquarters in Queens Avenue, Auburn (Melbourne). Isn’t ‘the Firthery’ a great handle?

Brock told me that Firth, who was into Monaros at the time, asked him what he knew about hot Holden sixpacks. ‘So I started talking about cams and heads and what have you with him and Ian Tate. They were very Ford-oriented, so the first specs we put in were basically what I had in the Holden panel van, the tow car – 113 Wade cam, clean up the heads, bigger valves and basically three inch-and-half SUs.’

Tate worked with Brock on such projects as choosing the right sort of air cleaner to drop onto the SUs. Then there were the brakes. ‘When you thrashed it really hard, it was very dicey on brakes. We reckoned it didn’t have enough boost, so we put the master cylinder and power brake booster off the Monaro 350 onto it.’ In the press release this is glossed over as ‘increased capacity booster’ – no need to mention the Monaro!

In 1987, Peter Brock looked back with some amusement at his 1969-70 ideas of setting up a suspension. The car, he said, ‘was just cobbled up. We did some camber change, we fine-tuned the springs, and shocks – but we knew nothing about it, let’s face it. We used to shift the sway bar on its U-clamps, loosen off the clamps and beat it with a hammer, then you’d nip it up and this was the heavy duty sway bar, you see. When the XU-1 finally came out, all those bits and pieces were incorporated.’

The Firthery took Brock’s advice but he had plenty of input himself. He was not just a brilliant ex-racer and a shrewd team manager – Ford Australia’s heavies must have come to rue the day they allowed the bloke who had orchestrated the 1965 (in a Cortina GT500) and 1967 (famously, in the XR Falcon GT versus much dearer Alfa Romeos) Bathurst victories to walk away – he also knew where to go for expert advice. When ‘Dyno Dave’ Bennett of Perfectune received an order from GMH for 250 cylinder heads, he assumed this was for some project involving the full-size Holden. It was, Bennett told me, ‘a year or so after’ he had convincingly demonstrated his Sprint GT version of the HR 186S; all the 186S needed was a Stage Two Perfectune head to transform it into what Bennett called ‘the 110 mph Holden for $130.’ The Sprint GT was two seconds quicker from zero to 100 mph than a standard XR Falcon GT!

Looking back, it is amazing how much difference ‘Dyno’ Dave Bennett’s lovingly improved cylinder head made to his HR 186S. Why hadn’t GMH insiders done similar work?

Is it possible that Dave Bennett’s enterprising project was a decisive factor in persuading the GMH marketing heavies to develop the 186 engine to a much higher state of tune and then instal it in the LC Torana – ‘LC’ standing for Light Car – as a better weapon for Bathurst than the Chevy-engined Monaro GTS, so heavy on brakes, tyres and fuel?

Every aspect of the XU-1’s carefully tailored specification cried ‘Bathurst’. The front spoiler, for example, not only aided stability but also channelled air onto the front discs. And consider the standard final drive ratio of 3.36, which was ideal for climbing the Mountain. And for those ‘enthusiasts’ who didn’t actually intend to enter the race, well, they could choose the optional 3.08 for slightly less hysterical cruising.

Because GMH still didn’t have its own four-speed gearbox, the XU-1 had to make do with the Opel unit, which was prone to failure when used hard. If there was a weakness in the XU-1’s armoury, this was it. But in practice the gearbox stood up OK, probably in part because the Torana was so much lighter than a Monaro, or even an HR 186S. Ratios were 3.43 for first yielding 36 mph at the 6400 rpm redline, 2.16 for second (58) and a tall 1.37 for third, allowing a marvellous 93 – just six mph short of the maximum speed in top of a Monaro GTS 186S. I owned one of those; wouldn’t I have just loved an XU-1? Top speed was 125, 400 rpm shy of the red zone.

Of course, I never got to own one and only had one test drive, back in about 1973 when a three year-old XU-1 – from memory, this was a purple LC – was just another used car. The example I drove felt electrifyingly quick in second gear where I had the sensation that it wanted to emulate an aeroplane and leave the tarmac. Compared with anything else I had driven, it was in a superior league for acceleration, and the engine sounded great, uynlike any Holden I had previously driven. It steered nicely. The ride was no better than awful and you still; had that narrow, cramped Torana feeling, ameliorated by the l-o-n-g bonnet. I can’t remember the asking price, but I still couldn’t afford it. I think I owned a Fiat 1500 Mark III at the time.

One judgement that I can make is that it was not as sophisticated a car as my HK Monaro GTS 186S. Perhaps one of the reasons I bought the Monaro was because I had been captivated by the image and ambience of the XU-1, but it was always a flawed road car, at least in LC guise. The purple paint had faded, too.

The LC GTR XU-1’s seats looked about three times as comfortable as they were.

In the end, the triple jugs were supplied by Zenith not SU. Maximum power was 160 brake horsepower at 5200 rpm with 190 lb/ft of torque at 3600. Could these numbers have been understated? GMH claimed 140 bhp for the X2 in 1965 but the changes to that were minimal compared with Harry’s effort. More likely, the 140 may in reality have been more like 130 or even 125. You’ve only got to look at where maximum power arrived – at 4600 in the HD X2, a remarkable 600 rpm lower than the XU-1’s peak.

While V8 Supercar racing has its merits, history is likely to show that the Series Production category did the most for the Australian automotive industry. The Cortina GT 500 is widely celebrated as the first proper Bathurst ‘special’ but it was completely overshadowed by the XR Falcon GT, the HK Monaro GTS 327, the GTR XU-1 and the E38 Charger. These cars are now highly sought-after classics with huge asking prices. It hasn’t always been so. As recently as 1995 I was recommending to a friend that he pay $12K for a good XU-1 to take club racing.

Good as the original LC XU-1 was, the Silver Fox (Harry Firth) had some more tricks up his sleeve for 1971.For that year’s Hardie-Ferodo, the LC XU-1 scored a heavier duty clutch, thicker front discs, a reworked cylinder head, new pistons and a wilder camshaft. Power swelled to 180 at a sky-high (for a Holden six) 6000 rpm. This car is generally referred to as the 1971 LC XU-1 Bathurst special.

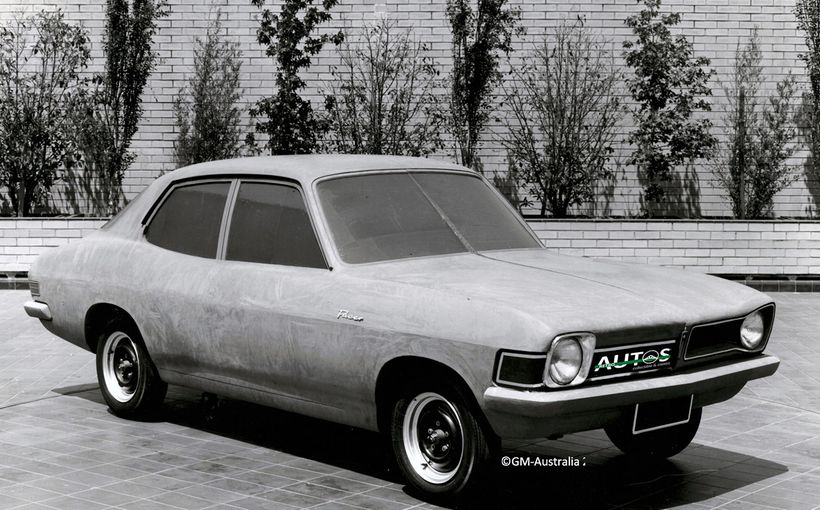

This press shot suggests the LJ XU-1 was too fast to get into focus.

Just five months later the LJ was introduced. With its eggcrate grille the new model looked neater and you could specify ‘houndstooth’ trim inside. But the biggest news items were all mechanical. The HQ’s 202 replaced the 186, but it was unlike anything ever seen beneath the bonnet of the bigger Holden. The compression ratio was 10.3 to one, 0.3 higher than the 1971 LC Bathurst special. Triple 1.75 Strombergs replaced the Zeniths. Peak power was now 190 at 5600 with 200 lb/ft at 4000.

A close-ratio M20 gearbox with taller ratios for the indirect gears took advantage of the 202’s extra power and torque. Maxima were 46, 67 and 98 (with 100-plus on offer for those brief moments of racetrack dicing).

As a road car the new XU-1 was far superior to the LC. In the early 1970s many competitors still drove their series production racers to the circuit. The LJ XU-1 could tackle the trip from, say, Melbourne to Bathurst in relative comfort. While the ride would never challenge an HQ’s for plushness, it was much improved over the previous car. Lowered spring rates and redesigned front seats together offered a literally palpable improvement: the tall driver could keep his bonce clear of the headlining! Nor did you need a mouthguard and kidney belt.

The LJ was not only faster but more civilised.

The fact that the new springs did not adversely affect handling suggests that the engineers and ‘engineer’ (read: Firth, Tate and Brock!) had made the LC too firm, too boy-racerish – OK for a smooth racetrack but horrible on the road. The LJ XU-1 was a much more civilised billycart.

During 1972 Harry Firth worked with GMH engineers on the V8 Torana project. This was never going to be called the XU-2. Former Holden executive Marc McInnes told me that the XU-2 code had been assigned to the Bedford truck division. ‘I rescued the paperwork – which hadn’t gone very far – and had XU-2 re-assigned to LH.’

Three XU-1 V8s were built before the media-induced supercar scare intimidated GMH, Ford Australia and Chrysler Australia into discontinuing their racing programs.

In time for Bathurst 1972 a limited batch of extra-hot LJ XU-1s was cooked. A wild ‘HX’ camshaft, light flywheels, alloy road wheels and revised suspension were key ingredients. The engine was balanced and blueprinted. Maximum power was 212 bhp. Peter Brock, however, was the main ingredient in this car’s Bathurst success.

Strike Me Pink was a hero LJ colour, which was also offered on lesser Toranas.

The final LJ rework came for 1973. About 150 cars scored a new tubular exhaust manifold designed by Perry’s. Dave Bennett did more work on the cylinder head. Larger valves, assorted upgraded engine components, heavy-duty axles and stronger brakes gave the XU-1 its swansong.

It is no wonder all Torana GTR-XU1s are cherished. They delighted Holden fans and probably many others as well as they outhandled and outbraked the heavyweight Falcon GTHOs at Mount Panorama and generally embarrassed the Ford drivers on tight circuits such as the much missed Amaroo Park and Oran Park. These sixpacks are legendary in their own right. The V8 could wait for LH, and did.

A lovely LJ XU-1 that was auctioned by Shannons.