Brough Superior 11-50: Honourably discharged

Story and Photos: Jim Scaysbrook Original Photos: John Rettig

Between them, the three 11-50 Brough Superiors featured here clocked up many thousands of miles in their duties with the Victorian Police Force. Up to 100 such machines (only 308 were produced) went into service throughout the state, along with a smaller number of SS80s, making Victoria one of the largest markets for the Nottingham (UK) manufacturer.

The Brough story itself began with William Brough, a coal miner whose formative years saw him experience the full force of the birth of motorised transport. One year before the beginning of the 20th century, Brough designed and built a motor car, followed by a motorised tricycle. The first motorcycle bearing the Brough name appeared in 1902, and William’s two sons, William Jnr and George, took a keen interest in their father’s products. In 1916, both teenage boys rode Brough machines in the ‘End to End’ Trial – from John O’Groats in Scotland to Lands End near Penzance in Cornwall. Young George struggled over the primitive roads and tracks with his peddle-assisted machine and managed to finish, while his brother took out a gold medal. The experience left a lasting impression on the lad, and although he later went into business with his father, he maintained that the company’s product was not all it could be. The father/son relationship was rather testy at times, as the youngster strove to foist his ideas on his rather implacable parent. After enduring this situation for few years, George made the decision to strike out on his own, with the mantra to create machines of the highest pedigree and standards of luxury – an altogether superior product to his father’s. Whether the Brough Superior appellation was a deliberate dig at his father is a matter that Brough junior felt disinclined to discuss, but his father certainly had his own views, commenting that the choice of brand name thereby made his own product the “Brough Inferior”!

Opening his new premises at Haydn Road, Nottingham in 1919, George’s machines immediately adopted the V-twin engine as their trademark (William Brough mainly used flat-twin engines) and the first machines were ready for customer delivery in early 1921. The very first Brough Superior used a 986 cc overhead-valve JAP engine and three-speed Sturmey Archer gearbox, Brampton front forks and a full lighting set with generator. At £175, it came at a premium price to match the excellent quality, which included extensive nickel plating. The handsome oval-sided teardrop fuel tank added to the model’s rakish good looks, and the first machine to be offered to the press for road testing produced rave reviews. A side-valve model, powered by a MAG engine and known as the SS80 soon followed, and at £150 in solo form or £180 with a sidecar, found plenty of buyers. The press dubbed the Brough Superiors ‘The Rolls Royce of Motorcycles’ and George certainly raised no objections to the compliment, which became the advertising catchcry of the brand in due course. In fact, much of the credit for the success must go to Ike Webb, the workshop manager and jack-of-all-trades who remained with George Brough for the entire history of the company. George himself was an enthusiastic user of his products, competing with distinction in trials and becoming an ace at Britain’s only permanent race track, Brooklands. The company usually managed to spring a surprise at the annual Olympia Show, and in 1924 it was the SS100, utilizing the new 50º JAP ohv engine. The mouth-watering model was based on the machine created for Bert le Vack, who continually established new speed records at Brooklands, and featured a new duplex cradle frame with Harley-Davidson inspired Castle forks (designed by George Brough and Harold Karslake, who had bought the fifth Brough Superior produced). Very soon after, an even more luxurious version, the Alpine Grand Sports, appeared, along with a racing version, the Pendine. Three years later, Brough teased the public with a four-cylinder model, the engine derived from a Lancia car design, exhibited at Olympia in a glass case, and with a whopping £250 price tag. It never went into production but probably achieved its aims via the immense publicity it attracted. The following year yet another four, this time a straight (longitudinal) design, was shown. Brough did however, go onto to produce a ‘four’ – the Austin-engine machine of 1932 with twin rear wheels, reverse gear and shaft drive, designed exclusively for sidecar use. There were also various JAP-powered smaller machines, the 680 and a 500.

So far no machine with a capacity greater than 1000 cc had been produced, but this changed in 1933 with the introduction of a 1096 cc model; the JAP engine manufactured to Brough’s specifications with a 60º included angle rather than the usual 50º. The model became officially known as the 11-50 (1100 cc 50 hp), featuring fully-enclosed side valves, quickly-detachable heads, bevel-driven magdyno and a roller bottom end. The 11-50 was available with either Castle or Monarch forks and in solo trim was capable of an impressive 90 mph. Best of all, from the buying public’s point of view, was the price - £99/12/6 – a Brough Superior for under one hundred quid! In 1934, a revised version, the 11-50 Special, appeared, with the magdyno now chain-driven (the bevel drive was deemed to be too noisy) and the valves behind a distinctive ribbed alloy cover. In standard trim the engine was fed through two mixing chambers fed by a single float bowl. The 11-50 Special, with its massive torque from the 5:1 compression engine, was tailor made for sidecar work, and despite a weight of more than 7 cwt (350 kg) was capable of a top speed of 72 mph.

Duty in the colonies

In the depressed years of the early 1930s, police forces in Australia, indeed world wide, employed motorcycles, both in solo and sidecar form, due to their ease of maintenance, economical running costs and durability. In Victoria, Coventry Eagles, powered by single and twin cylinder JAP engines, had been in service since the mid-1920s, but the firm was in deep trouble as the Depression bit and dropped its big twin in 1931 in favour of a range of frugal lightweights. Into the breach stepped Brough Superior, initially with the SS80 and later with the 11-50, and by the mid 1930s the big twins were familiar sights around Melbourne and regional areas, performing ceremonial duties as well as hunting down felons and ferrying senior policemen around in the sidecars. The big engine was truly a gem; capable of pulling cleanly away in top gear from as low as 12 mph – at which point the engine was merely ticking over at 760 rpm – and yet easily capable of attaining more than 70 mph fully-laden with rider and passenger.

The first 11-50s arrived for the Victorian Police Force in 1934, although sadly, official records no longer exist. The bikes in the initial deliveries featured hand gear change for the four speed gearbox – these were actually produced in 1933 as foot change was adopted for 1934. In accordance with the force’s contract, all sidecars fitted were locally-made Dustings. Had it not been for the war, Broughs would no doubt have gone on to continue a steady supply of machines to the Antiopdes, but by 1939 things were looking grim and the factory’s production capabilities were applied to the war effort, mainly making precision components for the Rolls Royce Merlin aero engines. A few machines were delivered by late 1939 and early 1940, and the very last Brough Superior motorcycle, an 11-50, left the works on July 2nd of that year. A prototype 1000cc 90º v-twin was built in 1944, using some AMC components, but never went into production. In total, only around 3,000 motorcycles were built between 1919 and 1940, and today are amongst the most collectable of all makes.

The Three Broughketeers.

Ex-police bikes have fuelled the motorcycle economy for ages. Many an aspiring ton-up boy got his start on an ex-police Triumph in the 1960s, but it goes back much further than that. Broughs were still in service post-war, at least in Victoria, but the big old V-twins were by then showing their age and were soon replaced by the modern breed of parallel twins, square fours, and later, flat twins in the form of BMW.

Around 1953, an ex-police 11-50 Brough was pushed under a house in Ringwood, Melbourne, and forgotten for over half a century. Since being decommissioned, it had been owned by a Mr Will Rackman, a square dance caller, who did his rounds of the country halls of Victoria on the big twin, and who also bought a spare 1939 11-50 engine and frame from the police at the same time. Eventually the magneto failed and the Brough was confined to the shed, while the sidecar was left in the backyard where Will’s son used it as a cubbyhouse. The 11-50 lay there in the dark, quietly decomposing, until Tasmanian John Rettig heard of its existence in 2004 and managed to acquire it, along with the spare engine. The handsome teardrop petrol tank was savaged by rust and the rest of the metal wore a distinctive russet tinge, but it was basically all there, and a challenge that John could simply not resist.

With the machine back in Hobart, John set about familiarising himself with the evolutions of the 11-50 and identified his example as a 1938 model, one of the last imported (a plunger frame version was catalogued for 1939 but few, if any, were imported). This machine has the chain-driven magneto and what is generally referred to as a Doll’s Head Norton-made gearbox, as used on the early International model but with different internal ratios and a special mainshaft. It also has Brough’s patented roll-on centre stand which is delightfully simple to use, and is fitted with Brampton front forks. The engine uses a single carburettor with twin fuel bowls. John’s restoration is superb without being over-done; the machine has won several awards since its completion.

John’s friend and near neighbour, Jack Overeem, who has a nice collection of machines that includes a Norton Commando, Matchless G9 and several later models, decided he simply had to have a Brough as well and went on the hunt, unearthing a second ex-Victorian Police bike. that had been restored 15 years previously. Jack’s machine is a 1934 model with bevel-driven magneto and Castle forks. It sports the distinctive Brough Perspex flyscreen and the similarly distinctive ‘hooded’ headlight shell.

Broughs attract Broughs, it would seem. Enter Peter Bender, another Hobart enthusiast whose business is a very successful fish-farming organization. Smitten with the Brough disease, Peter managed to convince Jack’s brother Casey Overeem to part with his 11-50. This particular bike had been discovered in Bendigo, where it had been banished to a leaky shed and was in a very sad state. Fred Fisher, who also owns an SS100 Brough, managed to extract the components from the owner and set about finding the missing parts, of which there were many. From there it passed to Casey and then to Peter, who decided to freshen up the restoration somewhat. This one is a 1935 model and is basically identical to the earlier model with the belt-drive magneto, but with Brampton forks and the battery mounted at the front of the engine. Like Jack’s bike, it has a single carburettor and float bowl.

A day on the green.

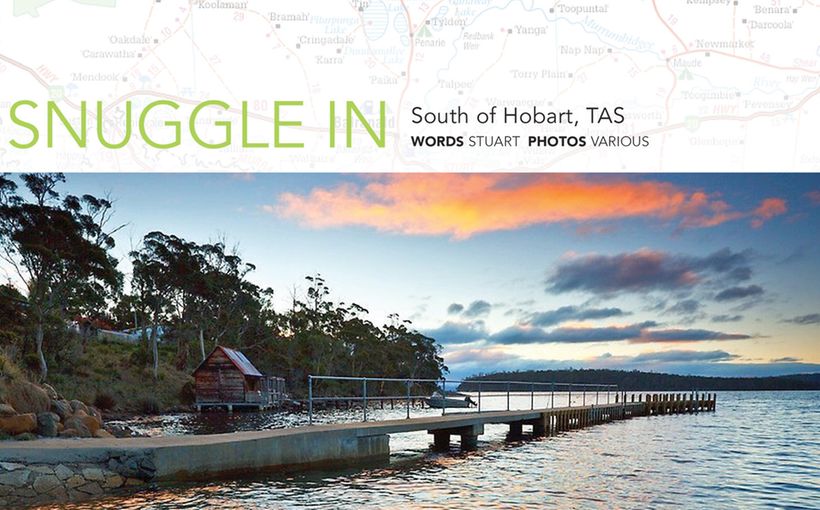

One sunny day in July, it was my privilege to journey to Jack’s home overlooking the Derwent River south of Hobart. Assembled on the lawn on a crisp but sunny winter’s day were all three 11-50s, and my education into the ins and outs of the model and all its subtleties was about to begin. The first lesson I learned was from looking at Peter’s bike, which arrived on a trailer. He had recently had the wheels rebuilt, and re-installation revealed that Brough wheels have a unique spoke pattern and a few degrees of offset, which had not been done. The result was two wheels several millimetres out of line, so this bike was a non-runner on the day. John rode his 11-50 to the photo location, and then planned to ride another 150 km to a vintage rally further south, accompanied by Jack (who chose to ride his Commando instead of the Brough). Jack’s 11-50 still started and ran perfectly, so there’s no doubt it would have been up for the trip.

With the static pictures taken, we set off for a lap around the neighbouring test track – a 10 km loop through hilly country on very good country roads. Here I had a chance to sample both John’s and Jack’s machines. “The front brake doesn’t work”, warned John, “but it doesn’t really matter because it has excellent engine braking and the rear brake is OK”. He was right, the front brake is totally useless, but the rest of the package is very pleasant indeed. The engine pulls strongly and if you take your time with the gearbox, changes are sweet and positive. This engine seemed to run a little sweeter than Jack’s, despite blowing a bit of smoke (due, John thinks, to a slightly mis-timed engine breather), and the Norton-based box certainly behaved better than the Sturmey Archer on the earlier model. The Castle forks on Jack’s bike seemed to offer more stable handling, but it too suffered slightly from the absence of a front stopper. Even with this flaw, I had a hard time keeping up with Jack as he flicked the model through the tight twists and roared up the quite steep hills. Side valve engines were always seen as poor cousins to the OHV jobs, but the 11-50 has so much power and torque that it’s fantasy to wish for anything else, especially when these simple powerplants are renowned for their durability and reliability. These are very usable machines – perfect rally bikes with an abundance of power, very good handling and a considerable degree of comfort. There’s even a hand-stitched leather case in which to keep the sherry for a post ride tipple! John Rettig recalls talking to an old gent at the Bendigo Swap Meet a few years back, who told him that when the first 11-50s arrived for police service the wallopers preferred the Coventry Eagles (fitted with the same JAP engine) and if you were late to the depot in the morning you would end up with a Brough! If that’s the case, then I can’t wait to ride a Coventry Eagle JAP – they really must be something because there is very little to wish for in an 11-50 Brough Superior, let me tell you!

Protect your Classic. Call Shannons Insurance on 13 46 46 to get a quote today.